Breaking the mold

When I was a young kid in the 1990s, a lot of my exposure to new media properties came from toys.

I wasn’t allowed much internet access at that age (I remember my dad having to sit me down after an attempt to find pictures of my favorite Spider-Man villain resulted in me just searching Yahoo! for images of “carnage”). I didn’t really buy comics. And video games were expensive.

Sure, I watched tons of TV and movies. But when I walked down the aisles of a Toys ‘R Us, I saw products for everything. Stuff that aired when I was in school or asleep, or when I was watching something else. Stuff that I wasn’t allowed to see. Stuff that I hadn’t even heard of. Those old big-box toy store shelves were a little kid’s equivalent of Ozymandias’ wall of screens - through them, it felt like we could survey the entire mediascape in a single afternoon.

At the same time, though, we were engaging with those media properties in a kinda funky way. After all, kids in a toy store aren’t looking for TV show recommendations, they’re looking for cool toys that look fun to play with. And the things that make cool toys aren’t necessarily in the source material.

For example, take this fella that I used to have:

The box said this was a “medusa dragon”. Its main features were those impressive wings (they came detached so that the toy could fit in its packaging), and the fact that one of its two heads could come off - so it was like this big dragon could launch off this little buddy. I have no clue what any of these features had to do with Medusa, but it looked cool.

The “medusa dragon” was part of the toy line made for the 1996 film DRAGONHEART, along with the “razorthorn dragon”, the “evil griffin”, and “Draco”. If something seems off to you about that list of names, well, that’s because Draco was the only dragon that was actually in the movie DRAGONHEART. In fact, the plot revolves around the fact that Draco is the only dragon alive. Those other three dragons aren’t even hinted at in DRAGONHEART, its sequel, or any of its three prequels. They were purely inventions of the tie-in toy line.

These days, that sort of thing seems unthinkable - imagine if the official toy line for the latest Spider-Man movie invented a bunch of brand-new characters that weren’t from any other comics or shows, and didn’t even appear in the film.

But…I kinda wish they would.

Let’s talk about when toy companies just made shit up.

Building playmates

For the last half-century, toys and visual media have had a much more reciprocal relationship than people tend to realize. Even among people who know that media like the original Transformers cartoons were made to promote the already-existing toy lines, there’s this tendency to view merchandise as a kind of capitalism-induced tumor on its associated property - something that feeds on the merits of the media, and eventually overwhelms and consumes it. The persistent rumor that George Lucas wrote the ewoks into RETURN OF THE JEDI just to be able to sell Star Wars-branded teddy bears to little kids is an enduring example of this line of thinking.

Don’t get me wrong: This kind of cynicism is a totally reasonable reaction to having our attention economy so overwhelmingly dominated by advertisers for nearly every waking second of our lives (even the existence of the term “attention economy” is pretty telling). When there’s a Funko Pop! figure of every frame from every movie or show you’ve ever watched - plus a special, uglier, limited-edition version of it that’s painted gold or some shit - it’s pretty easy to see toys as synecdoche for consumerism. The show (or whatever) you liked is the real art; the toy is just what they’re trying to sell you - right? Merch is how they repackage your interests and sell them back to you. Over and over and over again. Forever.

Sure, some of the broad strokes of that are true. But that show (or whatever) you liked is no less a commercial product than anything else…and making toys involves no less craft or art than making other forms of media.

Look at the story of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, recounted in a 2019 episode of the docuseries THE TOYS THAT MADE US.

The turtles debuted in 1984 with a self-published comic, written and illustrated by Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird. Then in 1987 Eastman and Laird scored a licensing deal with Playmates Toys, a Hong Kong-based company that had just recently expanded to the United States and was looking to launch a new action figure line.

The collaboration with Playmates Toys ended up producing most of what is recognizable about the property today - including the main cast’s archetypal personalities (leader, nerd, jerk, goof), color-coded costumes, and villains (Shredder originated in the comics, but had been killed off in the first issue “because we never thought there’d be another one,” Eastman explains).

The turtles’ appearance in 1984

The turtles’ appearance in 2012

I’m not saying that one of these versions of the turtles is better than the other. Both the original comics and the subsequent toy-driven incarnations are successful media in their own respective contexts.

The original comics were meant as a sort of mash-up of parodies of other comics (which is why the titular concept is an unwieldy jumble of unrelated adjectives). They were aimed at mature readers with enough media awareness to get the joke.

By contrast, the toy line was aimed at eight-year-olds. While the goal was always to sell as many toys as possible, it’s important to remember that most children that young aren’t collectors - so to sell them a bunch of related toys, you need to make sure they can easily tell the characters apart and intuit how they would interact with each other.

As Karl Aaronian (the senior VP of marketing at Playmates) puts it, in THE TOYS THAT MADE US: “Really, there’s a turtle for every kid. It’s kind of like THE BREAKFAST CLUB for action figures.”

The same principle applies in tons of children’s properties, as shown in this scene from BARBIE: PRINCESS CHARM SCHOOL

This isn’t just savvy product design, it’s also successful adaptation of a property to a new audience.

Concept developers at Playmates recognized that edgy irreverence was the core of the property, so to keep that essence they translated the comic’s grittiness into a more kid-friendly rudeness. This vaguely-toilet-humor-adjacent grunginess was borne out in the designs of Bebop and Rocksteady, two mainstay villains that were created for the toy line by comic artists working with toy developers.

Concept art by Peter Laird and Kevin Eastman of potential characters for the Playmates toy line (source)

Figure design by Mark Taylor for the character that would become Rocksteady, as shown in THE TOYS THAT MADE US

The final product produced by Playmates Toys in 1988, complete with a character bio in the packaging (source)

Merch is so often seen as the death knell of a media property, the maggots hatching in the corpse of art - but a lot of the time, the exact opposite is true. Some of the most beloved media properties of Millennial childhoods were, in one way or another, made by toys.

Physical fanfiction

In the late 1970s, George Lucas was trying to get toys made for the upcoming release of A NEW HOPE. After being turned down by industry giants like Hasbro and Mattel, the license ended up with the smaller-but-still-successful Kenner.

Writer and film critic Germain Lussier credits Kenner’s toy lines with a lot of the enduring success of the first three Star Wars films - not just because the merchandising was so successful that it helped pay for Lucasfilm’s growth, but also because the toys provided a way for people to keep engaging with the movies when they weren’t in theaters:

“It’s also important to remember this wasn’t a time when could simply rewatch the movies on VHS or something. If you wanted to relive the movie, the easiest way was to buy the toys and do it yourself. That made Star Wars toys everything to fans at the beginning. Their full-time connection to the movies. The way you kept the love alive in your heart.”

There’s a lot of truth to this, but I want to unpack the idea of “reliving the movie” a bit. For young kids playing with toys, there’s more to it than just recreating scenes exactly as they happen in the source material.

When I was around 8-10 years old and playing with Star Wars action figures, I don’t remember ever recreating a lightsaber duel between Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader - but I do remember playing a ton with this guy.

Figure from Kenner’s 1995 “Power of the Force” series. Photo by Dan Emmons

This is Bossk.

He appears in THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK and RETURN OF THE JEDI for about 24 seconds combined across both films. I don’t think he’s even named in the movies themselves. I absolutely did not remember this guy at all, even though I’d seen both movies multiple times before getting this toy.

I didn’t get this toy to recreate the scenes where Bossk stands in the background and does nothing.

Hell, I didn’t even get this toy to “relive” anything that was actually depicted in the movies themselves, really.

I got this toy because it looked cool, and I wanted to put it into my scenes - into the movies in my head.

Even when using licensed characters, a lot of play at that age is very inventive. The canon of the source material is often just a jumping-off point - at best.

In 1997, two sci-fi action movies came out that caught my attention: MEN IN BLACK and STARSHIP TROOPERS. Both had licensed toy tie-ins on release, made by Lewis Galoob Toys.

My parents took me to see MEN IN BLACK in theaters and I loved it. The only toy I got from it was a figure of the evil cockroach alien that had a belly pouch in which you could fit a little figurine of Tommy Lee Jones’ character, so you could recreate the scene from the climax where that guy bursts out of the alien’s gut. I got bored of reenacting that exact moment (both with the included figure and with other toys I had) pretty quick.

I wasn’t allowed to see STARSHIP TROOPERS because of the gore (I vividly remember one review that described the movie as being “only for everyone who likes raw meat for breakfast”). I got multiple toys from this movie, though, because they had a different figure for each of the different types of crazy alien bug that appeared in this movie. I wanted to learn more about this whole freaky ecosystem.

The Galoob toys overall hewed pretty close to the licensed material - but other companies were more imaginative, doing more of the sort of adaptation that Playmates had done with Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

The 1996 INDEPENDENCE DAY toy line put out by Trendmasters is a good example.

INDEPENDENCE DAY had exactly one type of alien, but Trendmasters released several variants of it. The version of the creature that appeared in the film was sold as an “attacker pilot” (and a bigger one was sold as the “supreme commander”) - but there was also a glittery lightning-blue one sold as a “shocktrooper”, a black one intended for “zero gravity”, a crimson “weapons expert”, etc.

This toy line fleshes out the “lore” of the film, but the goal isn’t to expand a rigid canon - the goal is to provide partially fleshed-out designs and concepts, to serve as inspirations for kids to use in their own play. The best analogy I can think of for this approach to merch is the concept of sourcebooks in tabletop roleplaying games like Dungeons & Dragons.

But the toy company that took this approach the farthest was, surprisingly, Kenner - the same company that started all this off with their screen-accurate Star Wars line in 1978.

Kenner Products, named after the street where their first factory was set up, was started in 1947. Before the Star Wars license, they were known more for their original toy lines (like Easy-Bake Oven and Stretch Armstrong).

For the first decade or so after A NEW HOPE’s release, Kenner’s licensed toy lines were exact recreations of their source material, from Star Wars to Batman. Starting with the toys made for the 1986 cartoon THE REAL GHOSTBUSTERS, they started some gentle additions of their own - some some new ghosts here, a new outfit there. By the 1990s, Kenner was willing to treat the licensed material almost as just a suggestion. It was Kenner that invented three new dragons to include in the toy line for a movie about the last dragon - but that was just a taste of things to come.

From 1992-1995, Kenner released several toy series intended as a tie-in to the 1986 film ALIENS in which they basically created their own version of the source material.

These toys were packaged with comics that were all connected, but these were extremely small vignettes more akin to the webisodes accompanying the Monster High doll line than the full-length Transformers comics that Marvel had put out. The human characters in these stories were technically lifted from ALIENS, but reimagined. Characters who died in the movie (i.e. virtually all of them) were resurrected in the toy line as roving exterminators who wandered from one planet to another, killing each new type of alien they found there with preposterous guns while wearing bright yellow “NO BUGS” shirts. Not only were these toys made for kids half the age of the movie’s intended audience - they would’ve been completely unrecognizable if you had seen the movie.

Bishop, the mild-mannered android science officer as he appeared in ALIENS

Bishop, as he appeared in the mini-comics packaged with Kenner’s ALIENS toy lines

Kenner also created two new characters, including a commando in a robo-suit designed to look like the aliens, but the good guys weren’t the real stars here.

Over the course of four collections, Kenner invented 15 new versions of the movie’s monsters. The company’s artists took the creature’s premise from the films - that its biology changed depending on which host species it parasitized - and made their own completely original designs that never appeared anywhere else (Kenner initially hoped to launch a tie-in TV series, but it never began production).

They had “boar” aliens with a mohawk of retractable horns. They had mantis aliens with claws so wicked and jagged it made the original creature’s design seem almost tame by comparison. They had a version of the badass alien queen from the climax of ALIENS that had huge clawed wings. There was a bug alien that had a different bug alien that it could shoot out of its head, and that alien had glowing red eyes that could light up. There was a monster for everyone.

This was officially-licensed, physical fanfiction. I fucking loved it. These toys are the reason why I got into this franchise, way before I would ever watch any movies in it.

Kenner also had the license for JURASSIC PARK, and they ended up taking that property to similarly crazy places.

The first products they put out were straightforwardly good toys. Recognizing that the appeal of JURASSIC PARK was just part of a much broader cultural fascination with dinosaurs, Kenner included not just the critters from the movie (Tyrannosaurus, Velociraptor, Triceratops, etc.) but also the ones that people would expect to see in a dinosaur toy line (Dimetrodon, Pterodactyl, Stegosaurus, etc.). They also included a bunch of much more obscure fauna - like Tanystropheus and Lycaenops - because paleoartists are the best kind of nerd, and each of the ones Kenner hired had their own list of less-famous prehistoric creatures they were excited to work on. Right off the bat, even Kenner’s vanilla stuff was bigger than the licensed material.

Then in 1998, Kenner debuted the “Chaos Effect” line of toys for the Jurassic Park series (the second movie, JURASSIC PARK: THE LOST WORLD, had come out the year before). Like the ALIENS toy line, this was intended to be released alongside a new TV series that was never made. The idea here was basically the same as in the later movies like JURASSIC WORLD and JURASSIC WORLD: FALLEN KINGDOM: the military had hired scientists to make extra-deadly new dinosaurs by mixing different species. Kenner’s concepts turned out to be much more exciting than we got in those movies, though. One of my favorites was “Amargospinus”, a mash-up of Amargasaurus and Spinosaurus - which definitely expanded what I thought a “cool” dinosaur was supposed to look like.

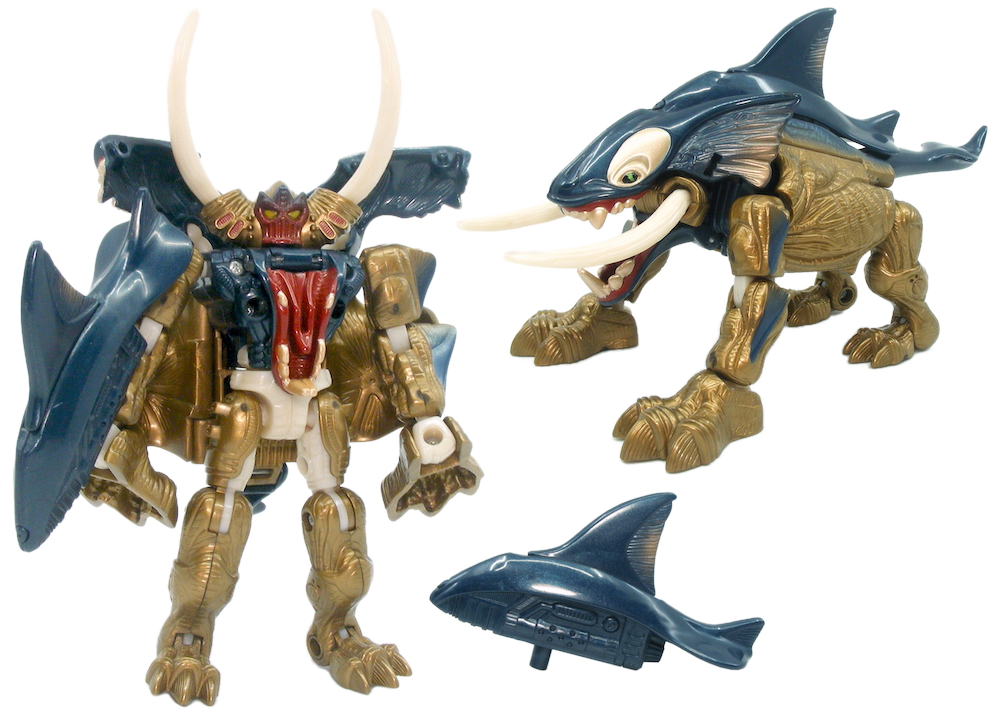

The last Kenner product line I want to mention is BEAST WARS - a.k.a. the toy line that saved Transformers when Hasbro (who had bought Kenner in 1991) said “Do something big with this franchise, or we’re cancelling it”. The resulting TV show and toy line were enormously successful and influential (my brother still has Dinobot’s existential crisis monologue memorized down to each individual snarl), but the specific toys I wanted to call attention to were their 1998 “Fuzors” lines - where Kenner designers mashed together different animals, just like they did in “Chaos Effect”, coming up with some real gnarly stuff - like “Torca”, a robot that turned into a cross between an elephant and a killer whale.

This sort of reckless inventiveness is what Kenner was all about in the 1990s. As I went back to look up these toys from my childhood, I’m kinda amazed how many of my favorites came from this one company. I can guarantee you that I never once went to my parents and said “I want a Kenner toy”, but there was a reason I kept asking for their stuff. Something special was going on there.

Loose canon

As it turns out, the same license that built Kenner up in the 70s and 80s would knock it down by the end of the 90s.

With the first new Star Wars film in 16 years about to drop, Hasbro had gone all-in on their tie-ins for the release of THE PHANTOM MENACE in 1999. It was soon clear that they’d drastically overproduced, though - and in late 2000, with analysts wailing “won’t someone please think of the shareholders?”, Hasbro axed their Kenner division. (Former employees also claim that Kenner was already on the chopping block after the “Chaos Effect” line didn’t sell well enough.) About 400 of the 500 Kenner staff were laid off, and its factory was shut down. In the announcement, Hasbro chairman Alan Hassenfeld said: “Today marks the first day of a new Hasbro”.

The new characters and creatures that Kenner originated for the Alien, Dragonheart, Ghostbusters, and Jurassic Park franchises never made it into any official shows or movies since then.

But they did make it into more toys.

Modern toy manufacturers NECA and Eaglemoss Collections both released official figures based on Kenner’s original designs for the ALIENS line. In both cases, the figures are brand new sculpts, rendering these monsters with all the additional detail afforded by modern manufacturing.

Part of NECA’s Kenner tribute in series 10 of their Alien figures, released in 2016

Eaglemoss’ take on Kenner’s mantis alien, sold as part of a “Retro Pack” in 2017

If you look at the hands on these modern renditions of the mantis alien, you can see an example of something kinda cool going on here. These figures are intended to be faithful recreations of a specific model - but since the only source material for this creature is a single toy, the artists ended up working their own distinct interpretations of it into their sculpts. Where the Eaglemoss figure has the alien’s hands end in long fingers, the NECA figure flattens the hands into something more like blades. Even in a “tribute” product, there’s still new creative input being added in.

The ill-fated “Chaos Effect” toys haven’t been commercially revived yet, but they are kept alive in fan works. In particular, the modding community for the 2018 game JURASSIC WORLD: EVOLUTION has become an outlet for fans to recreate their faves - even designs that were never actually released (like the Ultimasaurus, which was intended to be the star of the “Chaos Effect” line and even appeared on packaging for the other toys).

Kenner’s Ultimasaurus, realized by NexusMods user MrTroodon (available here)

Fan art of Kenner’s Amargospinus, made by Richard Kuulme (a.k.a. Hellraptor)

Regardless of their success as a business, Kenner was onto some good shit here, and it’s not just because these toys looked cool. (Which they did.)

There had been toy lines that reproduced existing properties in phenomenal detail, and there had been toy lines that originated brand new media properties - but for the last decade or so of the millennium, Kenner was originating new things within existing properties. Not only was this approach to licensed material exciting, I think it also showed a deep understanding of how young kids actually play.

To an eight-year-old, a property like Jurassic Park isn’t a canon - it’s a canvas.

Just like Playmates and Trendmasters, the designers at Kenner adapted their material by expressing its core themes (whether it’s “rude superheroes”, “biology-copying aliens”, or “genetically-modified chimera dinosaurs”) in forms that young kids could really grasp, in every sense of the word. The power of this approach is borne out not just by sales numbers, but by the fact that it can make even adult properties like ALIEN accessible to kids with single-digit ages.

You ever see a picture of a bunch of bootleg toys from a bunch of totally unrelated properties, all packaged together?

They’re funny as hell, but you know what?

That’s how kids actually play.

As a kid, I knocked all my toys together. From around ages 8 to 13, I built a sprawling plastic cosmology - one with multiple universes, different kinds of afterlife, apocalypses, and retcons.

The main cast of characters in my stories revolved around a sort of “pantheon” of my favorite toys, the final incarnation of which included the 1991 Hasbro figure of Scorpion from Mortal Kombat, Buzzclaw from Kenner’s 1998 “Fuzors” line of Beast Wars toys (except I replaced his arms with ones from Hasbro’s 1998 “Mega Ax” transforming Animorph figure), an unpainted figurine of Duo Maxwell that came with the 1997 “Deathscythe-Hell” Gundam model kit from Bandai, and a black-costumed Spider-Man figure that ToyBiz put out in 2001.

My stories usually borrowed from the media that these toys came from. In Mortal Kombat, Scorpion is a vengeful ninja from hell - so my multiverse had to include hell, and my version of Scorpion was also from there. But the longer I played, the more everything developed into its own distinct world - the original backstories for these characters became subsumed completely by my history of playing with them. The black Spider-Man figure was the godhead of my multiverse, for instance (because he had the most points of articulation) - and his character’s name was “Smooth Criminal”, because Alien Ant Farm’s cover of Smooth Criminal had just come out and immediately became my favorite song.

Through these toys, I was “reliving” my favorite media by playing with the concepts in it as raw materials, stretching the parts I loved until they filled my world.

I could go on forever recounting just the parts of these sagas that I remember, but we’ve all done this sort of thing, in whatever medium we’re most engaged in - from toys to fanart to ask-blogs on Tumblr to fanfiction to TikToks, and more.

In a post-Marvel-Cinematic-Universe-world, consumers tend to think of bodies of narrative media as being brands - and therefore, have started expecting a tightly-managed consistency from these works.

The question of “what’s canon?” has been around since way before the MCU. When you’re talking about a collection of stories as vast as “Star Wars”, it’s useful to have a recognizable and somewhat-consistent record of what that includes. But the current cultural fixation over “canon” is absolutely an outgrowth of a corporate fixation on “brand integrity”.

In 2017, Hasbro released a line of Star Wars dolls called “Forces of Destiny” aimed at young kids (ages 4 and up). Like Kenner’s ALIENS line, these were accompanied by installments of short-form media meant to explain the characters (in this case, it’s webisodes again) - but this time, it’s all canon, which is an absolutely wild concept if you think about it. A six-year-old isn’t going to care that it’s impossible for Padme and Rey to play together in canon (and don’t even tell them what happens to Jyn Erso in the movies).

Video essayist Jenny Nicholson has an excellent breakdown of the problems with Hasbro and Disney’s approach to “Forces of Destiny”, which you should absolutely check out.

When I think of the primacy we’re giving to a brand-centric, corporate version of canon - even when it comes to media for young children - I find myself thinking about THE LEGO MOVIE.

The movie’s villain, President Business, wants to keep every other character in a fixed context, segregated by brand and product line. His obsession with enforcing canon leads him to try to superglue every Lego character in place - essentially destroying their utility as toys. This, says THE LEGO MOVIE, is wrong. The message is clear: play supersedes canon, and that’s a good thing.

THE LEGO MOVIE was widely well-received, with many critics praising its message in particular. But at the same time, the overwhelming brandification of narrative properties has led to a lot of discourse that implicitly assumes that President Business was right: what matters most is canon.

And sure, having major films exist in a “shared universe” is fun and exciting. But the movies that speak to me the most are the ones like INTO THE SPIDER-VERSE - whose canonicity is irrelevant, and whose message is that these stories and characters are for everyone.

There’s a lot more stuff I love about THE LEGO MOVIE, most of which has been said before - but there’s one thing in particular that really resonated with me, which I don’t see commented on quite as much. It comes up in a scene near the beginning, where President Business shows off a vault full of powerful artifacts with strange names.

These are all mundane pieces of garbage - the “Sword of Exact Zero” is the blade of an X-Acto knife, the “Po-Leesh Remover of Nah’iiyl” is nail polish remover, the “Cloak of Ban-da-Yeed” is an old bandaid, etc. But their intended functions get recontextualized as lore in the movie’s world - for example, the “Sword of Exact Zero” becomes a mythical relic that can cut through everything.

That scene, maybe even more than the movie’s finale, showed me that the filmmakers really “get it”. A major element of play is moving things outside of their intended context.

That’s how kids make stories with toys.

And for a couple years there, it was how one of the more famous toy companies made monsters for those stories.