Hating the player

Spoiler warning

This article will discuss endings and major narrative elements for the following games:

FAR CRY 4 (technically)

UNDERTALE

IMSCARED: A PIXELATED NIGHTMARE

INSCRYPTION

DOKI DOKI LITERATURE CLUB!

MOON: REMIX RPG ADVENTURE (but don’t worry about it)

Oh, and I guess a silly little quest from SKYRIM. Let’s start with that one.

“I hope it was important”

One of my clearest memories from my first playthrough of SKYRIM is of a quest called “Blood's Honor”. I mentioned it briefly earlier, but I wanna go into a bit more detail here - because that quest was almost one of my favorite moments in the game.

“Blood’s Honor” is part of the questline for the Companions, a brotherhood of do-gooders for hire with an emphasis on honor and bravery in combat. Their leader is a likable, wizened old warrior named Kodlak. When other Companions are ready to exact violent revenge, Kodlak counsels against needless bloodshed.

In other words, Kodlak is a pretty chill dude, and the moral core of the Companions.

As I get more involved with the Companions, I discover a secret history: the inner circle of the brotherhood, including Kodlak, were all cursed to be werewolves. Some of the Companions think being a werewolf is awesome, but not Kodlak.

Kodlak is weary and ready to die. And while normal humans join their ancestors in the afterlife, werewolves spend eternity as beasts in an endless hunt. Having lived a long life full of battle, what Kodlak wants now is rest. He wants to be reunited with his family and heroes.

Eventually, Kodlak asks to speak in private.

He’s discovered a cure, and it requires the head of one of the evil witches that originally cursed the Companions. Having gotten to like the guy, I agree to help lift his curse.

I make it to the cave with the witches, and the game gives me an optional objective: Wipe out all the witches, not just the one I need to cure Kodlak. Given my experience with open-world RPGs, it feels like the game is asking me to make a choice: how much needless bloodshed will I indulge?

Of course, I choose to kill them all. They’re basically pure evil, right? And combat is fun. Typical RPG stuff. I take the extra time to exterminate every witch, murder all their pets, and loot every corner of their cave, before returning home.

When I get back, a heartbroken Companion angrily greets me with a “Where have you been?!” It turns out that while I was gone, a group of werewolf hunters had attacked the Companions…and in the ensuing battle, Kodlak was killed before I could cure him. I betrayed the values Kodlak tried to impart to me, and in doing so, damned Kodlak himself. “I hope it was important”, the Companion spits.

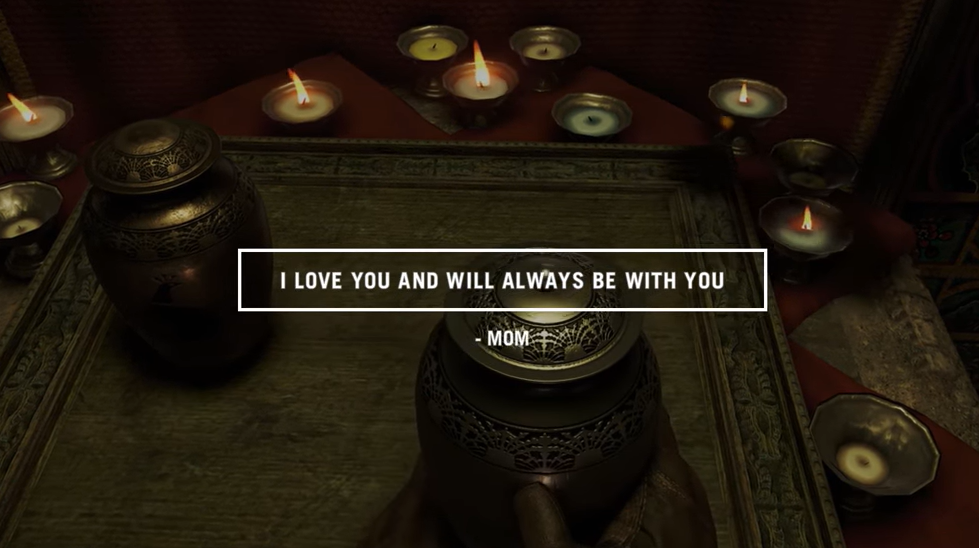

Kodlak’s death, recreated in a mod by NexusMods user GruffDaddy (source)

This moment actually gets to me. Enough so, in fact, that I load an earlier save file in order to do things differently. The second time, I don’t kill all the witches, and return as quickly as I can.

And it’s at this point I discover that Kodlak’s death had nothing to do with my “decision”. Kodlak always dies, and you always go kill the werewolf hunters in retaliation (even though it’s the sort of thing Kodlak wouldn’t have wanted), and then you always get to cure his soul of the werewolf curse after death.

“Blood’s Honor” went from memorable to deflating just by reloading my save and playing it again.

To be fair, this is a pretty generic quest as far as these things go. If I hadn’t read too much into the fact that killing all the witches was “optional”, I might not have assumed I could change the outcome. (It even turns out that Kodlak has a piece of dialog where he specifically asks you to kill all the witches - I just hadn’t encountered it.) But something still sticks out to me from this whole experience.

The second time I played “Blood’s Honor”, when the Companion demanded to know “Where have you been?!”, I remember thinking:

“What’re you mad at me for? I didn’t write this quest.”

So.

Let’s talk about games that wanna make you feel bad for the stuff you do in them.

Intended disobedience

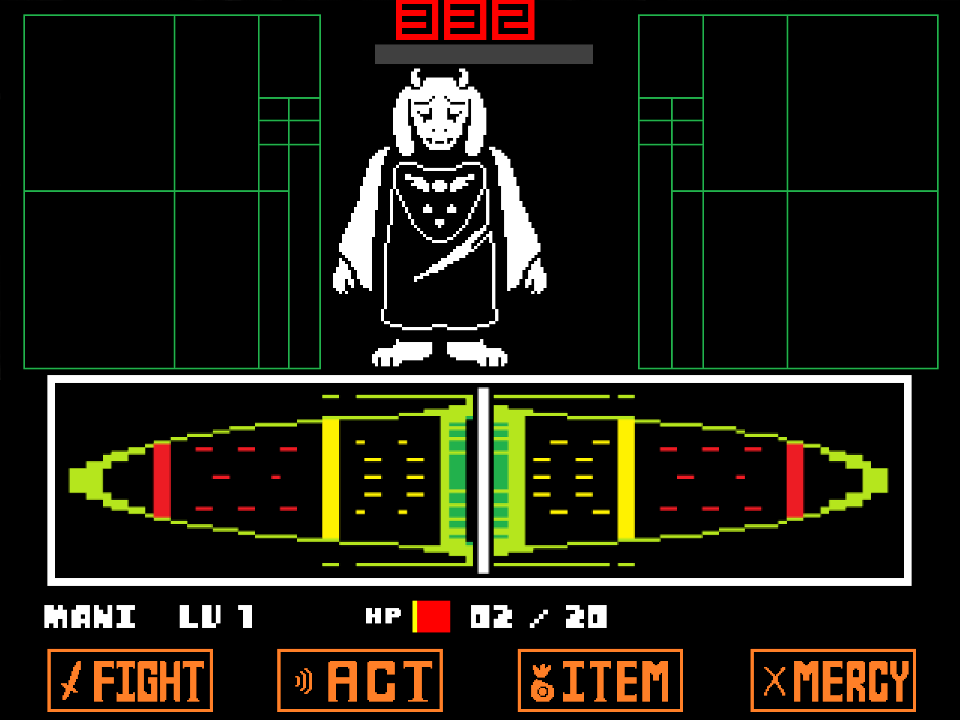

Unlike SKYRIM, some of the most memorable moments in UNDERTALE are the direct result of reloading a save file. And for a lot of first time players, one of these moments comes up pretty early on.

Toriel is one of the first characters you meet in UNDERTALE, and she’s a sweetheart. She saves you from an evil flower (named Flowey), she gives you a home with your own room, and she bakes you pies.

She’s also the game’s first boss battle, as her desire to protect you leads her to try to stop you from leaving the first area of the game. Despite this, the battle feels more like having an argument with a parent than a fight to the death (she even tells you to go to your room!). Surely nothing bad will happen. She’s only the tutorial boss.

And then you land that last hit, and Toriel dies.

She falls to one knee, winces through her goodbyes, and just dies right in front of you.

It’s sad.

You feel sad.

So you reload your save file from before the fight. This time, you find another way to end the fight. You reach an understanding, she gives you one last warm hug, and then you leave. You fixed things.

And then, on your way out of the tutorial zone, Flowey the murderous flower shows up, and drops this on you:

“I know what you did. You murdered her. And then you went back, because you regretted it.”

This is the moment that the game reveals two things to you:

The game has a pseudo-4th-wall-breaking narrative that tracks player actions like “loading a specific save file”

A major theme of the game will be assigning moral value to “normal” player behavior in games (like depleting an enemy’s health bar)

That second thing is what makes UNDERTALE’s approach to moralizing player decisions different from other games with “good” and “bad” choices (such as MASS EFFECT). Unlike those titles, UNDERTALE is saying something about how we play games; the narrative is explicitly addressing player actions like “loading a save file after doing something bad”.

Flowey describes the ability to reload earlier saves as “the ability to play God” - and the rest of the game agrees with him. When another character becomes aware of the player’s ability to save & reload, they describe the experience as agonizing (“You can’t understand how this feels. Knowing that one day, without any warning...it’s all going to be reset.”). Flowey himself says he used to be able to save & reload the game, and that eventually led to him wanting to kill everyone and everything out of boredom (“not out of any desire for good or evil,” as one character puts it, “but just because you think you can. And because you ‘can’…you ‘have to’.”).

You’ve probably heard of this before. This is the sort of stuff that UNDERTALE is famous for.

Now, instead of talking about whether it’s bad to be mean to characters in games, or whether it’s wrong to want to wring every last piece of content from a game, I want to start with a different question:

How does UNDERTALE intend you to play it?

Even though the game does want you to feel bad for killing Toriel, the takeaway here isn’t just “you’re supposed to spare Toriel” - you’re very much intended to kill her, too.

The reality of games is that any result of a player choice that produces game content is an intended outcome - what media critic Dan Olson calls “intended play” - even when other elements of the game appear to suggest that you’re not “supposed” to do that.

In other words: “What does the game intend you to do?” isn’t as simple as “What does the game tell you to do?”

A fun example here is FAR CRY 4. The very first thing the game tells you is the protagonist’s narrative goal: return to his mother’s home country and place her ashes at his sister’s grave. When he arrives there, the country’s bloodthirsty tyrant (Pagan Min) invites the protagonist to a meal. Partway through the meal, Min gets up to take a phone call - while instructing the protagonist to “stay right here, enjoy the crab rangoon,” and wait for him to return - after which, the player gets control of the protagonist, letting them immediately run off, get caught up in the rebellion, and ultimately depose Min.

But the fastest way to complete the protagonist’s narrative goal is to obey Min, and just wait: when he returns from his phone call, Min leads the protagonist straight to their sister’s grave, they place their mother’s ashes while some soulful music plays, and the game ends.

Virtually all of the gameplay in FAR CRY 4 is the result of the player ignoring the first goal they are given. This dynamic is also basically the entire premise of THE STANLEY PARABLE, an indie game where the player controls a character named Stanley who receives instructions from a disembodied narrator. The more the player contradicts these instructions, the more frustrated the narrator gets, and the more they chide Stanley and try to steer them toward the “right” path. Just as in FAR CRY 4, the player’s “disobedience” is clearly intended, and THE STANLEY PARABLE constantly calls attention to this fact. In one section, Stanley can end up in a white void outside the level. For a moment, there’s silence…and then the voice-over narration resumes: “At first, Stanley assumed he had broken the map, until he heard this narration and realized it was a part of the game’s design all along.”

Expecting player disobedience isn’t just for gags, though.

After the opening segment of THE LEGEND OF ZELDA: BREATH OF THE WILD, you are tasked with saving Princess Zelda, who is locked in combat with the evil Ganon. Through dialog, the game tells you that her strength is waning, and she may perish at any moment - so you must rush to her rescue, before Ganon covers the world in darkness. But the game fully expects you to ignore this goal for most of your playtime, as you run around catching horses and baking cakes and photographing bugs and doing everything there is to do in the world other than saving it. This sort of faux-deadline (Zelda never actually falls to Ganon, no matter how much time you take) is extremely common in games, particularly in RPGs and open world games. Just like in FAR CRY 4, ignoring the game’s direction is…basically the whole game.

Again, Dan Olson summarizes it well:

“If there is crafted content on the other side of your misbehavior, then it’s not actually misbehavior.”

I could fill this article with examples, but anyone who’s played enough video games already understands this on some level. If you’ve ever spent any time testing the boundaries of a game, or even just been unsure of what to do in a particular section, you’ve probably discovered that the only real way to know that you’re not intended to do something in a game is if you try to do it…and nothing happens. Everything else you do that the game actually rewards with a tailored response, therefore, is intended.

This might seem weird when some of these intended outcomes are “bad”. For example, the survival horror game NIGHTCRY has 32 unique endings - but 25 of them involve your character dying and the game ending prematurely (i.e. without discovering the whole story and stopping the villain), making them essentially more fleshed-out versions of the variety of unique death animations in games like DEAD SPACE. In these games, the unique content associated with dying in different situations makes those deaths intended outcomes - after all, someone playing a horror game is signing up to see terrible things be done to people - but the player is obviously meant to understand these outcomes as “bad” and to be avoided. At least from the second time onward.

The punchline here is that a game’s intended play can include contradictory incentives and outcomes - and when we analyze games, we need to consider all of them. The point I’m making isn’t that obeying Min is what you’re “really” supposed to do in FAR CRY 4 because it resolves your narrative goal the fastest; it’s that both obeying him and disobeying him are intended play.

This is especially important in games like UNDERTALE, which not only address the player directly but attempt to comment on their decisions as the player. Some decisions are “good”, some are “bad”, but all are intended.

Intended shame

UNDERTALE is one of those games where the protagonist is sporadically attacked by monsters. When most people play UNDERTALE for the first time, they usually end up killing at least some of these monsters - it’s just how these games go. At first, the player is unlikely to think much of it. But as the game goes on, UNDERTALE draws more and more attention to these actions.

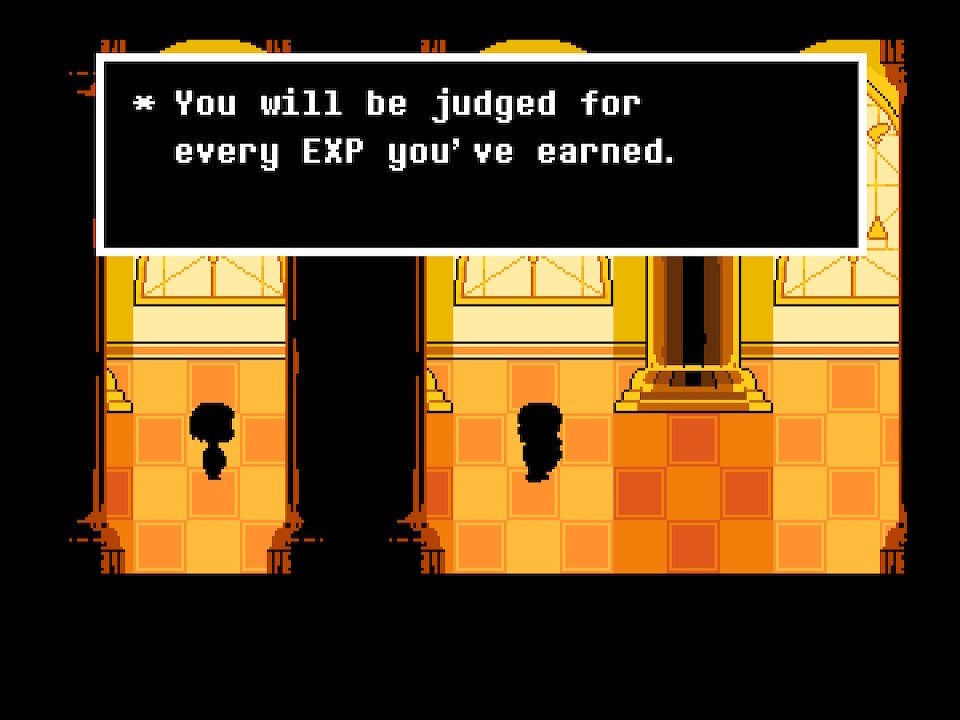

You start noticing empty seats in restaurants where the monsters you didn’t spare would be sitting next to their friends. Certain characters refuse to talk to you. The parent of monsters you killed ask you “Have you seen my son?” And eventually, Sans - a character initially introduced as comic relief - explains to the player that some of the game’s mechanical terms secretly had darker meanings all along (e.g. “EXP”, a pretty conventional shorthand for “experience points” that represent general progression in most games, actually means “execution points” in UNDERTALE: “a way of quantifying the pain you have inflicted on others”).

The over-the-top-ness of the “hall of judgment” scene seems to be at least partly intended for comedic effect (after all, if you keep talking to Sans here, he says things like “You killed some people on purpose, didn’t you? That’s probably bad,” before concluding with a wink and a “Anyways, don’t do that”), but the message is still clear.

At the end of your first playthrough, Flowey - the evil flower who remembers your actions even after reloading a save file - reveals himself as the game’s final boss in a memorable sequence full of fourth-wall-breaking as he tries to “take over the game” (doing things like promising to reload save files so that they can kill the protagonist over and over forever). Defeating him earns you some “what everyone’s up to now” dialog before the ending credits roll.

And then UNDERTALE’s real commentary begins.

When you start a new playthrough after this point, Flowey appears and gives the player direct guidance on how to get “a better ending”: befriend every major character through side-quests, and avoid killing any enemy or boss. At the end of this “pacifist” route through the game, you have a very different final confrontation against Flowey - one whose emotional climax reveals that Flowey’s antagonism ultimately comes from a fear of closure: they want to keep killing the protagonist over and over again so that the player will keep playing the game forever, and never have to leave their old friend Flowey behind.

After forcing Flowey to admit this, the protagonist can finally give Flowey the comfort they needed to be able to let go. And you finally get that “better ending”, full of animations showing every character achieving their dreams. Birds are singing, flowers are blooming, and everything’s perfect.

When you launch the game again after this ending, Flowey asks the player not to play UNDERTALE anymore. Everyone got what they wanted. Starting a new game means taking that away from them. Why would you want to do that?

Well.

Because there’s more content.

If killing no-one gets a special ending, what about killing everyone?

If you play through UNDERTALE while killing every enemy and boss, you get to experience a very different version of the game. The “genocide” route of the game (as fans call it) uses every trick it can to make you feel bad: completing it requires killing your friends; whole towns that were full of life are instead depopulated; some bosses plead for their lives; other bosses go down in one hit without a fight (making the victory feel more like cruelty than achievement). You are the game’s villain now - wreaking as much havoc as you can just to see what happens, exactly as Flowey used to do before you started playing.

The narrative condemnation of these actions even extends past that save file. Future playthroughs are tainted by a completed “genocide” run - even the wholesome sunshine-and-rainbows ending sequence mentioned earlier concludes in sinister images referencing the player’s darker choices. Just like Flowey’s dialog after killing-then-reloading Toriel, the game is saying “I know what you did”.

And all of this, as much as the game seems to shame you for indulging in it, is still intended play.

If both “pacifism” and “genocide” are intended play, does that mean the game is contradicting itself?

Not necessarily: both the “pacifist” and “genocide” routes of UNDERTALE are saying the same things. The game’s theme of “accepting closure and moving onto something new” gets articulated whether your actions reinforce it (e.g. by having your protagonist communicate it to other characters, or even by obeying the request to stop playing) or reject it (e.g. by “taking away everyone’s happy ending” when you reset the game, or by killing everyone just for the additional content).

But using shame to relay a message is playing with fire - and UNDERTALE does get burned a bit.

In games, people are going to resent being made to feel bad about something they were incentivized to do. And the incentive to kill everyone in UNDERTALE goes beyond just “to see what happens”.

When you reach the “hall of judgment” in a “genocide” run, Sans doesn’t just admonish you - he actually fights you. And he is the most challenging and exciting battle in the game, by far. Everything about this fight is exhilarating: the writing is dramatic, the music is legendarily a certified fucking bop, and the fight itself is wild. Make no mistake: this fight is the reason why Sans is the most popular character from UNDERTALE by a huge margin.

Fan art by DeviantArt user Pdubbsquared (source)

By contrast, the final boss of the “pacifist” run isn’t really challenging at all - in fact, you can’t lose: each time you would die, the game instead fully heals you, and after a certain point the fight essentially becomes an interactive cutscene. If the thing you like most about UNDERTALE is challenging boss fights, then the “genocide” route is the “better ending”.

On the one hand, this makes sense. “Pacifist” runs are all about story, featuring lengthy text-heavy sequences as you befriend everyone; a cinematic final battle that’s more “cinematic” than “battle” is a fitting conclusion to a playthrough that’s all about refusing to fight. Meanwhile, the “genocide” route is almost hidden (the game doesn’t suggest killing everyone unless you’ve already been doing that for the whole first section), so UNDERTALE is joining in a long tradition of having super hard secret bosses - where the reward for jumping through a series of obscure/tricky hoops is a unique gameplay challenge.

But on the other hand, the hoops are all saying you’re being a big meanie for jumping through them, and that muddies the messaging of the game in a kinda unpleasant way. The motivator for a “genocide” run isn’t just more content - it’s specifically content that the developer went out of their way to make extremely fun. And shaming your players for wanting to enjoy the most fun parts of your game is a dicey proposition.

Shame is extremely compelling - after all, that brief experience of it was enough to burn an otherwise forgettable SKYRIM quest into my memory. But a lot of the time, shame is an anti-motivator: If you try to shame someone into accepting a certain viewpoint, you’ll often find that the easiest way for them to avoid that shame is actually to reject your viewpoint.

In other words, when some players hear the most fun boss in UNDERTALE say things like “if we’re really friends, you won’t come back”, their reaction is gonna be:

“What’re you mad at me for? I didn’t design this fight to be awesome.”

This is the risk that comes with putting intended shame into your game.

Some of my good friends who really dislike UNDERTALE call it “manipulative”. What they’re talking about isn’t just that the game is engineered to elicit a specific emotional response from you - it’s the bait-and-switch-y feel of the way it sets up incentives and scolds you for following them.

This isn’t just about the Sans fight, either. Looking under the hood of the Toriel fight is pretty revealing.

In battle, Toriel has much more health and deals much more damage than any enemy fought before her. However, once the player’s health is low enough her attacks will intentionally miss the player. Now the player is in full control of how to end the fight: they can keep attacking Toriel, or they can try using their “Mercy” action. (They can also flee, but this accomplishes nothing since Toriel must be defeated in order to progress.)

If the player keeps fighting, then after a handful of attacks the game will secretly adjust Toriel’s stats so that the next hit finishes her off regardless of how much health she had left.

If the player wants to avoid killing Toriel, meanwhile, they need to use their “Mercy” action 24 times.

Yes, the game is asking you to weigh your options - but it’s got its fingers on the scale. This is done purposefully: by making the outcome of this fight likely to be a surprise, UNDERTALE is teaching the player that their assumptions about how to play the game might not hold true. Lots of games feature this sort of magic trick, where they deliberately mislead you in order to teach you something.

When the game breaks the fourth wall to shame the player directly, though, the spotlight on that magic trick is much brighter - which increases the odds that the player sees past the misdirection, and resents the magician.

Spooky spaghetti

Breaking the fourth wall isn’t unique to games like UNDERTALE - but these kinds of games have a particular relationship to that narrative device. To explain that, I need to talk about another major theme of UNDERTALE:

Spaghetti.

Official Steam trading card for UNDERTALE. Art by Linnet

“Creepypasta” has become an umbrella term for urban-legend-style, “this-really-happened” horror stories that are primarily circulated online. (The name comes from “copypasta”, a slang term for stories that get copied and pasted from one community to another.) Creepypasta characters like Slender Man earned the genre some mainstream fame in the early-to-mid 2010s, but that’s just one outgrowth of what was going on at that time.

Creepypasta had been around before the 2010s - Slender Man originated in 2009, for example - but the creation of Creepypasta.com (in 2008), the Creepypasta Wiki (in 2010), and the subreddit r/NoSleep (also in 2010) created more stable communities, along with centralized platforms where people could promote their work to a larger audience.

Creepypastas about video games were both common and popular at this time, usually drawing on the nostalgia that the authors of these stories (often millennials) had for the pixel art games of the 1980s and 1990s. This subgenre of creepypasta is best exemplified by the untitled “NES Godzilla creepypasta” (released in 2011), where the protagonist plays a haunted copy of the 1988 game GODZILLA: MONSTER OF MONSTERS! - one that asks them probing personal questions, and confronts them with freaky monsters that shouldn’t be in the game (all of which are creations of the story’s author, user Cosbydaf from the now-defunct forums at Bogleech).

The rise of these creepypasta communities also coincided with the launch of a new wave of sites dedicated to sharing and forming communities around indie games and fan-made game content, like GameJolt (in 2008) and itch.io (in 2013). These sites made it even easier for small games made by tiny developers to get widely circulated, especially if they got noticed by a major influencer. Notably, it was much easier to get a cheap or free game listed on one of these sites than on the Steam marketplace.

You can see this whole ecosystem play out with the story of SONIC.EXE:

In 2011, user JC the Hyena wrote a story about a haunted Sonic the Hedgehog game and uploaded it to the Creepypasta Wiki

In 2012, user MY5TCrimson made a playable version of the game described in that story, SONIC.EXE, and uploaded it to GameJolt

In 2013, world-famous YouTuber PewDiePie recorded himself playing SONIC.EXE and uploaded it to his channel, putting it in front of millions of viewers outside the creepypasta community

In 2015, MY5TCrimson uploads the final version of SONIC.EXE (version 7) to GameJolt before announcing they’re trying to stop being the SONIC.EXE guy

As of 2022, searching for “sonic.exe” on GameJolt turns up over 1,000 games - including spinoffs, knockoffs, sequels, parodies, and even completely unrelated games that use art or music from SONIC.EXE

At the same time, similar trends were playing out in other communities - like the newly-formed adult fandom of the 2010 show MY LITTLE PONY: FRIENDSHIP IS MAGIC. 2011 saw the launch of Equestria Daily, which quickly became a lightning rod for fan content - including the darker stuff that some bronies were starting to put out. “Evil games” almost instantly became a popular genre here. These games were typically extremely short, usually trying to act like real-life versions of the haunted games from creepypasta stories by doing things games “shouldn’t do” (like making the game window unable to be closed, leaving a freaky image stuck on the screen). Some took it a step further, and made explicit fourth-wall-breaking an element of their horror. The DREAMY RAINBOW games that came out in 2011 (recently attributed to YouTube user Yukitoshii) are good examples. They start as simple platformers, then characters warn you not to play further, then the game starts addressing the player by name (gleaned from reading their operating system) and creating new files with creepy messages in them.

Finally, THE STANLEY PARABLE also came out in 2011 and received near-instant critical praise, prompting a commercial remake in 2013. THE STANLEY PARABLE doesn’t really have any creepypasta-related origins, and there probably wasn’t a ton of overlap between between the sort of people who read Ars Technica essays about existentialism in games and the folks who download gory pony games from Equestria Daily - but THE STANLEY PARABLE’s success nonetheless further cemented fourth-wall-breaking as a Thing™, no matter which particular scene you followed.

When you put everything together: The 2010s saw an explosion of cheap-or-free indie horror games, a surge of new and recognizable source material to base them on, and a huge incentive toward attention-grabbing gimmicks - and all these elements dovetailed into an emphasis on breaking the fourth wall specifically to seem creepy or invasive (or, at least, subversive).

When UNDERTALE came out in 2015 (after nearly 3 years in development), it was very much an heir to all these specific trends in 2010s indie games:

Self-aware characters that address the player directly

Juxtaposition of cutesy characters and sinister tones

Nostalgia for pixel art games of millennials’ childhoods (in this case, 1991’s BRANDISH and 1994’s EARTHBOUND)

And messing with the conventional boundaries of game interfaces

Despite not being a horror game, UNDERTALE still features some deliberate creepypasta-style horror moments. There are grayed-out versions of characters that have a less-than-1% chance of appearing in your game, who say eerie things before disappearing. One of the endings has a jumpscare where a character says “Since when were you the one in control?” before rushing at the screen. Oh, and the official art book confirms that Flowey’s design in UNDERTALE was partly inspired by a character from the NES Godzilla creepypasta.

But while the fourth-wall-breaking in UNDERTALE is evolutionarily related to the stuff you see in these horror games, it’s still pretty different - kinda like foxes and dogs. To flesh this out a bit, let’s take a look at a couple of these other games.

IMSCARED: A PIXELATED NIGHTMARE is an indie horror game released in 2016, following the success of a much smaller initial version released in 2012 (and with a remake in the works for 2022). The game mostly functions as a typical first-person key hunt through creepy hallways and bloodstained rooms, until it starts deliberately crashing and resetting itself - while writing new files to your computer that contain clues on how to proceed, as well as messages from the game’s antagonist (a sentient program named White Face). Gradually, you learn that the game’s erratic behavior is the result of White Face trying to have fun with you - like Flowey, White Face wants to play forever.

Eventually, IMSCARED gives you a choice: either proceed to the game’s true ending, or allow White Face to delete your save data so that you can start over and keep playing together. If you choose the former, White Face confronts you one last time, both furious and terrified by your decision:

“I begged you, and you ignored my request! What do you think will happen next? You made this game unplayable - I made this game unplayable - I don’t want to die! I’m scared...”

At this point, the game consists only of a single room in which White Face attacks you, crashing the game each time it reaches you. The only way to reach the true ending is to exit the game and delete White Face’s “heart” (in the form of a new file added to your computer called heart.txt, which includes White Face’s final farewell). After doing so, the next time you load the game, the rest of the game’s content is permanently walled off, leaving you with only an empty environment to walk around in.

Despite some superficial similarities, IMSCARED’s commentary ends up pretty different from UNDERTALE’s. IMSCARED is a horror game, and main function of the fourth-wall-breaking isn’t to comment on the player’s decisions but to create an unsettling experience by blurring the assumed boundaries of the game. White Face’s pleas are there to help sell the illusion of a sentient computer program in order to make the player uncomfortable - they’re not meant to make you regret or reflect on your gameplay choices. You get a little bit of backstory for White Face, but they’re never really presented as sympathetic or someone for you to connect to.

Some time after the success of the initial version of IMSCARED (Markiplier and PewDiePie promoted it in late 2012), indie developer Daniel Mullins was working on a horror game with a similar premise: a game whose digital guts you had to pick apart in order to figure out how to progress. He first made PONY ISLAND as part of a 48-hour game jam in 2014, and after some encouraging reception, fleshed it out for commercial release in 2016. Thanks to a signal boost from PewDiePie, Daniel Mullins Games became an overnight success - and has been making creepy fourth-wall-breaking games with built-in digital scavenger hunts ever since.

Their latest game, 2021’s INSCRYPTION, received a fair amount of hype on release - so let’s take a look at it as a more recent example of these kinds of games.

In INSCRYPTION, you play as Luke - a fictional YouTuber who discovers the only copy of a digital card game called “Inscryption”. The four main characters of “Inscryption” (the fictional game) are aware that they are characters in a game, and are constantly jockeying for control of that game while Luke plays it - with the winner of each power struggle temporarily rewriting the game to center around them. The gameplay mixes rogue-like deckbuilding with escape-the-room style puzzles, and it’s all tied together with some simple and decently-executed found footage scenes (for that classic “real life urban legend” flavor).

The disk containing “Inscryption” also contains a special code hidden within it (the “OLD_DATA”), which turns out to be one of those terrible secrets that must not be released into the world. Ultimately, one of the self-aware characters decides to delete the game itself in order to bury this malicious code - and the finale consists of each character saying their goodbyes as “Inscryption” destroys itself. The highpoint of this sequence is a rematch with the villain of the INSCRYPTION’s first act (i.e. the first character to have “taken over the game”), who reveals that - you guessed it - they just wanted to play with you. They’re revealed to be a lore junkie and casual gamer at heart, and as their world ends around them the only thing they want to do is have one last friendly match. They even stop tracking points, just to keep playing as long as they can. When their time is up, they offer you a surprisingly warm “Good game” and a final handshake before they’re ripped from existence in a red flash.

This could’ve been where INSCCRYPTION ended. But there’s still one last character on the disk, and they’re much less serene about all this. The last opponent you bid farewell to (who is also the character you’ve talked to the least throughout the game) has some choice words for Luke about everything that’s going down:

“Why not simply eject the disk, Luke? Spare me and whatever is left? Ah, but I have foreseen it. You do not eject the disk. You have to know what comes next.”

Now, INSCRYPTION is an interesting case here. Unlike UNDERTALE or IMSCARED, the player isn’t playing as themselves (they’re playing as Luke), and they can’t change the ending of the game. But despite this, the game still comes across as judging the player for their actions in a way that feels like a clumsy rehash of IMSCARED.

We never really learn enough about Luke to feel like we’re really “inhabiting” him as a character. (In fact, you don’t even find out that you’re playing as Luke until about halfway through the game.) Meanwhile, the moments where the game breaks the fourth wall are still so prominent and frequent that it’s easy to forget they’re technically addressing Luke. For example, later in the game INSCRYPTION starts reading unrelated files from your computer and referencing your Steam friends list, but you’re supposed to understand that those are Luke’s files and Luke’s friends. Topping all this off, Luke himself doesn’t seem to believe the fourth-wall-breaking stuff in the game, either: the final found-footage scenes (after “Inscryption” deletes itself) show Luke talking to a reporter about the game like it was just a weird piece of malware, not a miraculously self-aware piece of programming.

So by the time INSCRYPTION’s final character is blaming the person on the other side of the screen for their impending death, the game’s premise is in a strange lose-lose situation when it comes to how you’re supposed to read it. Either everyone’s talking to Luke, in which case the game’s telling you to treat the fourth-wall-breaking stuff as a sham - or everyone’s talking to you, in which case the game is guilting you for things you literally had no control over.

When your match against the last remaining character is interrupted by the game’s self-destruct process, they collapse to the floor, crawling feebly towards you to offer that last handshake - only to be abruptly deleted without comfort or closure. It’s made to look pitiable. Between that and the whole “you could save me but you won’t” bit, the game clearly wants you to feel bad for this character.

But it doesn’t work. Again…

“What’re you mad at me for? I didn’t do anything.”

I don’t think INSCRYPTION was really trying to shame you for playing it all the way through - it was probably just trying to dial up the creep-factor a bit at the end. But it stumbles into that feeling anyway, which pulls an otherwise awesome game down a notch or two. By replicating the aesthetics of mid-2010s indie horror games but without giving the player control over the outcome, or characters to get attached to, it reaps the downsides of UNDERTALE’s moralizing while missing out on the potential benefits.

Imagine someone handed you a book that says “I’m dumb”, told you to read it, and then went “Ha! You said you’re dumb!” It’s that SKYRIM quest all over again.

But there is at least one indie game out there that pulls this stuff off, and actually manages to stick the landing.

Hating the game

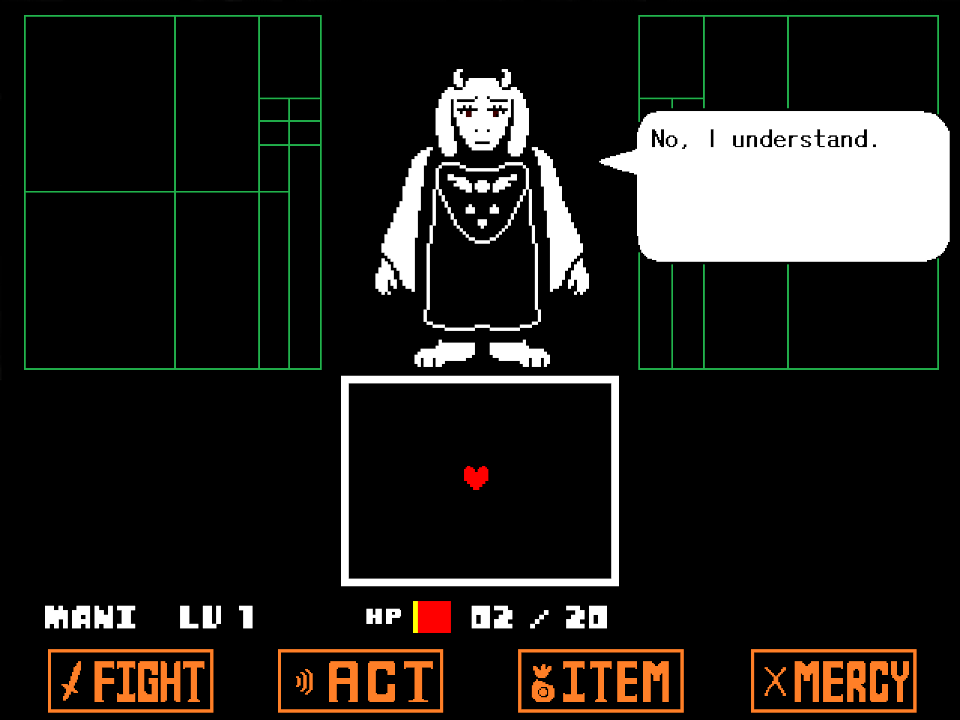

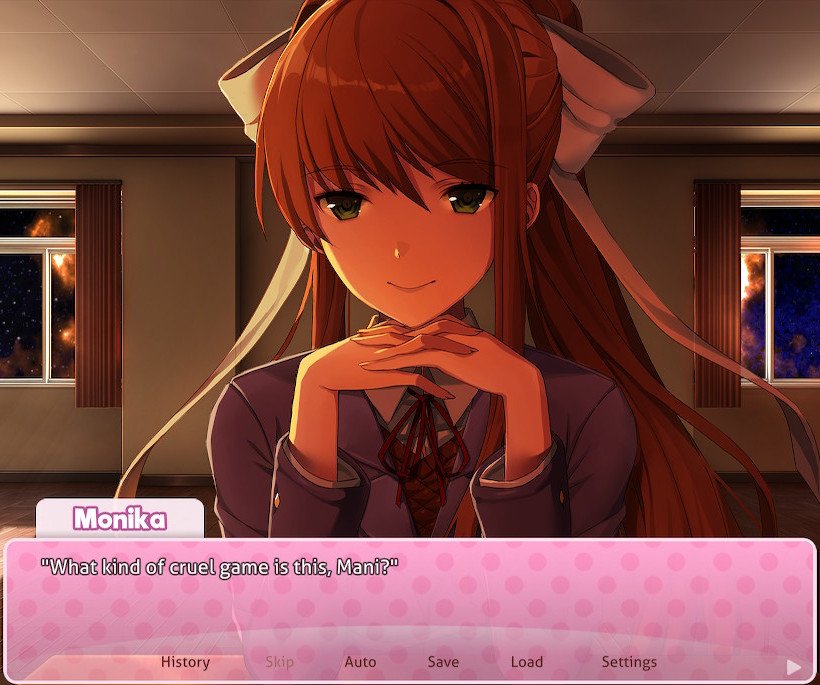

DOKI DOKI LITERATURE CLUB! is an indie horror game where - stop me if you’ve heard this one - a self-aware character breaks the fourth wall and starts “messing with the game” in order to spend more time with the player. This time, the game is a dating sim, and the self-aware antagonist is Monika - who wants to force the protagonist to choose her as their romantic interest.

Once Monika realizes she is in a game, she stops seeing the other characters as her friends, and becomes capable of incredible cruelty to them, just like Flowey. Ultimately, Monika deletes every other character in the game, reducing DOKI DOKI LITERATURE CLUB! to a single room with you and Monika. At this point, just like in IMSCARED, the way to complete the game is to go into the game’s directory and delete Monika’s files.

At first, this plays out similarly - with Monika lashing out: “How could you? How could you do this to me? You were all I had left…I sacrificed everything for us to be together. Everything.” Some of her final dialog directly echoes sentiments from the battle with Sans, too:

“I never thought anyone could be as horrible as you are. You win, okay? You win. You killed everyone. I hope you’re happy. There’s nothing left now. You can stop playing.”

But that’s not the note that DOKI DOKI LITERATURE CLUB! ends on.

In the closest thing to actual self-awareness that occurs in any of the games I’ve mentioned so far, Monika then asks what would make the player do this. She begins to blame herself, not the player, for this outcome. She regrets her actions, and even starts walking back some of the self-aware, fourth-wall-breaking cynicism that led her to treat the other characters in the game as just code: “I really…did love the Literature Club.”

Monika makes one last attempt to twist the game’s code into producing a happy ending, but it also fails. Ultimately, she realizes that a happy ending isn’t possible in the game - that it’s the game’s fault things end up this way. Neither she nor the player ever had the ability to really change it.

DOKI DOKI LITERATURE CLUB! then begins to delete itself. But unlike INSCRYPTION, the final sentiment isn’t a clumsy “please don’t let me die” from a stranger - it’s a “thank you” from a character you spent a lot of time with as she says goodbye. The song that plays over these final credits is tender and sweet, full of regret but also hopefulness. After it finishes, Monika’s final message is one of appreciation: “For the time it lasted, I want to thank you.”

This right here? This works. And not just because it’s being “nice” to the player.

During Monika’s perspective-shift from “hating the player” to “hating the game”, she admits that she couldn’t actually find it in herself to permanently delete her friends - and in doing so, Monika spells out the message at the heart of DOKI DOKI LITERATURE CLUB!:

“Even though I knew they weren’t real…they were still my friends. And I loved them all.”

The fourth-wall-breaking in DOKI DOKI LITERATURE CLUB! is ultimately an expression of earnestness, not cynicism. The game is about the power of emotionally connecting to fictional characters, no matter how silly. (For more on this, check out my review.) This is a sentiment it shares with UNDERTALE, too. Yes, Flowey is violent and cruel within the fiction - but that’s the metaphor, not the punchline. The reason Flowey is the villain isn’t because video games are like WESTWORLD and it’s morally wrong to be mean to video game characters; he’s the villain because he stopped earnestly engaging with the characters (among other things). Towards the end of a “genocide” run, Flowey explains the moment he stopped caring about his friends: “Their companionship was amusing...for a while. As time repeated, people proved themselves predictable. What would this person say if I gave them this? What would they do if I said this to them? Once you know the answer, that's it. That's all they are.” This, UNDERTALE says, is what Flowey is wrong about.

So…could UNDERTALE have gotten its themes across without dedicating an entire route to shaming the player?

Well…maybe.

Toby Fox, the lead developer for UNDERTALE, mentioned drawing inspiration for the game’s story from a 1997 game called MOON: RPG REMIX ADVENTURE. (In a funny turn of events, Fox had never played the game himself, as it hadn’t been released outside of Japan - but UNDERTALE’s success led to Toby talking to MOON’s developer, which led to the game getting translated and released internationally in 2020 - over two decades after its development.) MOON begins with a boy playing a parody of typical RPGs of the time, where he controls a hero who is tasked to kill an evil dragon. After a short sequence poking fun at RPG tropes, the boy gets sucked into the world of the game - but not as the hero. Instead, the boy is a ghost possessing the clothes of someone’s dead grandson, and your goal is to help him restore love to the world by saving the souls of all the creatures slaughtered by the hero.

MOON’s commentary is fine for what it is. It has some sincere themes about the way heroism is portrayed in games that go beyond just parodying its genre (the 2020 release was marketed as an “anti-RPG”). What’s missing, though, is emotional impact. Rescuing the souls of slain animals doesn’t really change the world around you so much as it makes your level go up - which is the same motivation as the murderous “hero” that’s terrorizing everyone. At the end of the game, the final choice you’re asked to make to save its world is literally to stop playing it, but this moment rings a little hollow because you haven’t really experienced the version of the world where your gameplay was what was torturing it (aside from that brief series of gags at the very beginning).

Both DOKI DOKI LITERATURE CLUB! and UNDERTALE, by contrast, invest you emotionally in their themes by allowing you to actually play the experience of a world changed by loss.

In DOKI DOKI LITERATURE CLUB!, this happens in the second “loop” - when you play through the game after your best friend Sayori died. The most powerful moments of this section of the game are when you play through the scenes when Sayori would’ve shown up, but now is gone - the walk to school in the morning, the first invitation to join the Literature Club, etc. The game flashes some distorted visuals and text in these moments, partly for some good old creepypasta vibes, but the real function of that is to draw attention to Sayori’s absence - an absence you feel, because you played through the version of the game that had her in it.

In UNDERTALE, this effect is achieved when you pursue a “genocide” route after having completed a “pacifist” run, which the game is designed to make more likely by actively encouraging the latter while “hiding” the former. In a “pacifist” run, you get to goof off with all the colorful enemies, get to know all of your friends, and just generally appreciate all the warmth and charm of the game’s world. During a “genocide” run, your actions leave the world empty - and that emptiness is felt, each time you enter a store that’s been abandoned, or walk past a spot where a friend would’ve called you and had a funny conversation. Conveying these emotional experiences through interaction is one of the unique strengths of games as a medium, and sometimes that means playing through the unpleasantness of the “bad route”.

Now…could UNDERTALE have gotten all that across without calling you a big meanie for enjoying the super cool Sans fight?

Well…again, maybe.

For all his sanctimonious dialog during it, the fight against Sans is a much needed piece of fun. This adds some conflicting incentives, but I’m honestly not sure that the “genocide” route would be a better experience overall if it were mono-downer the whole way through. Either way, though, that would be a very different game - and we won’t really understand UNDERTALE better by speculating about it.

UNDERTALE is what it is, and it is that on purpose.

Besides, the developer is already moving on.

True reset

Toby Fox is currently working on UNDERTALE’s spiritual successor, DELTARUNE. The first part of it was coyly released under the guise of being a “survey program” on Halloween 2018 (can’t shake those creepypasta instincts, eh?). A continuation was released in 2021, along with the announcement that the full game will have 5-7 chapters total. DELTARUNE features the “same” characters as UNDERTALE (e.g. there’s still a skeleton named Sans in it), but with entirely different backstories and in a new setting. It also introduces brand new main characters.

This game isn’t “just more UNDERTALE”, though.

At the beginning of Chapter 1, DELTARUNE repeats a few times that the player’s choices don’t matter, and I think that emphasis is telling.

Right after Chapter 1’s release, Fox tweeted an FAQ of sorts about the project and its relation to UNDERTALE. In it, he said: “If you played UNDERTALE, I don't think I can make anything that makes you feel ‘that way’ again.” There’s a lot going on in that statement, and I don’t want to claim to know the inner workings of Fox’s heart. Part of it is definitely that Fox is trying to head off some expectations about DELTARUNE imposed by UNDERTALE’s success - and nostalgia-tinted expectations have a habit of eclipsing any possible reality that follows. But so far, the characters and world of DELTARUNE are just as rich and charming as those in UNDERTALE; it’s still an emotional and touching game. So when I see Fox saying that DELTARUNE won’t make you feel “that way”…it’s hard for me not to read it as, partly, talking about the intense emotions provoked by UNDERTALE’s metafictional commentary on actions like “resetting after the happy ending” or “killing characters to see what happens”.

UNDERTALE clearly shows a deep understanding of the inherent pull of new content. (For example, one of the clues that Toriel can be spared is that each of the 24 times you try to do so, she says something new…suggesting that you are, in fact, getting somewhere.) Fox knows that simply by putting a fully fleshed-out “bad route” into the game, he is providing a motivator to pursue it that can’t be completely overridden by any amount of discouragement within the game. It’s all intended play.

But that leads to the next conclusion, which is that parts of the game are intended to make you feel bad - that some of the incentive structures in the game are built to point you toward shame.

Personally, I love UNDERTALE. But it’s totally reasonable to resent it for being made this way. There’s no single “right” way to react to a game. It’s important to emphasize this, both in light of UNDERTALE’s immense popularity (which leads a lot of people to be dicks to those who don’t like it) and to better understand how games like UNDERTALE create these feelings to begin with. If the number of “Game of the Year” nods that INSCRYPTION earned is any indication, there’s still plenty of appetite for this flavor of fourth-wall-breaking. And a remake of THE STANLEY PARABLE is also currently in development. So it’s worth really thinking about this stuff.

People who don’t enjoy UNDERTALE because it feels “manipulative”, or who just don’t like being made to feel bad, aren’t somehow failing to appreciate the game or its messages or how it tries to convey them or any of that. These feelings are, unavoidably, a risk that comes with this approach to communicating meaning through gameplay. There’s lots of dials and knobs that creators can use to tweak that risk and its outcomes, but it can’t be erased completely.

In the years since its release, UNDERTALE may have become most famous for its “bad route” (again, just look at why Sans is its most popular character). If that’s the case, it may have unintentionally sabotaged its own message - because that type of fame is pretty likely to encourage people to scrutinize DELTARUNE in a way that’s detached from its characters and story. When you pull off a novel narrative trick that goes viral, folks show up to your next performance with antibodies (just ask M. Night Shyamalan). In a post-UNDERTALE world, people are going to jump into DELTARUNE looking for a “genocide” route.

So it makes sense to me that DELTARUNE begins by saying “don’t do that”.

Immediately after DELTARUNE’s release, Fox tweeted that “No matter what you do the ending will be the same.” A year later, in an interview with Nintendo, he said that the inspiration for DELTARUNE was a dream he had in 2011 where he vividly saw the ending to a game, and since then he’s been trying to make the game that reaches that one specific ending.

Fox didn’t even begin UNDERTALE until he decided he needed to put DELTARUNE on ice for a while, and felt a need to “prove to myself it was possible” to finish a game in the meantime as a tiny indie dev.

UNDERTALE was just the game Fox (along with artist Temmie Chang) made in the midst of an internet fixation on creepy fourth-wall-breaking.

DELTARUNE is a different game, and a different dream.

There’s a lot more that could be said about DELTARUNE’s first two chapters - even some things that directly relate to things I talked about in this piece - but I won’t be going into that now. For the time being, I’m happy to just enjoy what’s been released so far (it’s very good). I don’t want to spoil that stuff here, but also…the game isn’t finished yet.

Despite rampant fan speculation about DELTARUNE’s connection to obscure characters from UNDERTALE’s lore, we don’t actually know if DELTARUNE will share any of its predecessor’s messages or metafictional devices or horror sensibilities.

So far, the thing about DELTARUNE that’s most evocative of the “haunted media” stories of the 2010s is just the way Toby Fox talks about the project itself:

“For the past 3 years I’ve been waking up in the middle of the night unable to go back to sleep because I’ve been thinking about the scenes that happen in the game. [...] If I don’t show you what I’m thinking, I’ll lose my mind.”