Skyrim vs. Witcher 3, part 3: Mechanics and Meaning

Welcome back to the series where I attempt to redeem how much time I spent playing SKYRIM and WITCHER 3 by spending even more time talking about them, and how they are (or aren’t) good examples of open-world RPGs.

Part one was about the setting of each game, since they’re strikingly similar at the start and set up the potential consequences for your conquests.

Part two covered morality systems, which are prominent outgrowths of the “you can be whatever you want” pitch that these sorts of games make.

In this part, I’m going to talk about the story of each of these games, which means I have to talk about their gameplay mechanics.

And if that sounds a little weird, lemme explain.

When talking about media, people often approach questions like “Is the story good?” by recounting the list of things that happened, in order, and then evaluating them piecemeal: which ones were believable, which ones were badass, which ones were memorable, etc. This is sort of a “listicle” approach to analyzing a story, with all the connotations of “optimized for viewership” that the word “listicle” carries. For instance, the highly successful YouTube comedy review channel CinemaSins approaches their critiques pretty much strictly in this way - turning each movie into just a string of events that get scored individually.

(As a result, these thought criminals consistently do shit like ask a question at one point in the film that is answered in another point in the film. CinemaSins is basically instructions on how to watch movies wrong, and no I’m not taking questions at this time. But this is a great explainer.)

But a story isn’t just a series of things that happen - it’s also how they’re told. There’s no story that exists without a medium, and that specific medium always shapes how the story is conveyed.

In print media like books and comics, this involves things like the path of the eye across the page, as well as when the reader turns the page.

A page from Mark Danielewski’s HOUSE OF LEAVES (sloppy annotations by Mani Cavalieri). The widening paragraphs and spacing injected into sentences and words both slow you down and give you a sense of an emptiness opening up, until there’s so much of it that your eyes follow a path that completely ignores normal line breaks, eventually tracing a sentence that literally splits apart. It’s disorienting, but still using the reader’s intuitive eye movements for effect. Most books aren’t this inventive with their page layout (and this book gets much wilder than this), but that doesn’t mean they do nothing. There’s a reason that the final chapter of ANGELA’S ASHES by Frank McCourt is just a single word.

A page from BACKSTAGERS (vol. 1, act 2), written by James Tynion and illustrated by Rian Sygh (and again, messily annotated by Mani Cavalieri). The top panel leads you from text (left) to the faces of the birds (right), and you reset to the left side of the page in panel two. There, the movement of the characters reinforces the direction your eyes move (again left to right) into panel three. One of the characters is looking directly at where your eyes will go next on the page - to the left side of panel four, where the text is - before the characters’ expressions and the flashlight both direct you to where you’re about to physically touch to turn the page and see what they’re looking at.

Digital-native media like webcomics can combine those things with other elements, like how an image loads on a browser, and how you have to scroll to travel down it.

A single panel from Emily Carroll’s short comic HIS FACE ALL RED. The border of the panel becomes the border of the hole. By placing a character regularly along the way, the artist gets us to slow down as we scroll down (because there’s something visually engaging to look at instead of just a hole). Our slowed descent down an unusually long single image builds suspense, and the tension isn’t fully relieved when we get to the bottom. The silhouette of the thing at the bottom of the hole again becomes the contour of the panel, keeping it completely “off-screen”…for now. You can (and should) read the whole comic for free here.

I could spend even more time going over all the conventions used in film, but I really need to get to the next major point here - so for now, I just want to note that there’s actually a pretty widespread understanding of many basic elements of filmic storytelling like “what’s in the frame” and “how is the camera moving”. People who haven’t studied movies at all will still know what a “close-up” is, and have reasonable guesses about when it might be used.

This scene from a little-known film called PSYCHO showcases a standard convention for conversations, called shot/reverse-shot: the image cuts back and forth between two shots - one for each participant - often when that one is talking. Eventually, the shots become close-ups that are more directly facing the characters, as the conversation becomes more intense - with one character even leaning further into the frame, before eventually leaning back as he cools down a bit.

And video games?

The biggest unique element of how video games tell stories is through gameplay.

Although there’s a shit-ton of incredibly clever and passionate people that are both talking about and making video games, the medium is still very young (we’re just two generations out from the first video games - compared to about five generations for movies, at least eight generations for comics, and I’m-not-gonna-bother-counting-how-many for novels). The basic elements of how gameplay tells stories aren’t widely understood yet - at least, not anywhere near the degree that they are for movies and TV. So you still have lots of gamers who genuinely think that “story” and “gameplay” are two entirely separate and not-necessarily-related parts of story-driven games.

And to be fair to them, there’s plenty of game developers who think that too, and make their games believing that the story is only what’s happening in the cutscenes.

But the reality is that the way you play the game does still shape how you digest the story. Delivering 99% of your plot in cutscenes at the end of levels, for instance, will mean that the plot will be seen as either a reward for gameplay or a barrier to gameplay (i.e. something to suffer through before you get control again), which will affect things like how much you care about the characters and how you receive the messages of the story.

So this essay is going to compare the basic story for SKYRIM and WITCHER 3, and look at how it plays out as you, well, play the game. And since both of these games have reams and reams of worldbuilding and lore and character biographies, I’m going to focus on one element in particular:

You.

That is, the player.

In both of these games, the character you control is a hero of mythic proportions, someone who gains incredible power in order to rise to the challenge of thwarting global annihilation. And not only that, but both of these games start the hero in a world that appears to be in decline. Major institutions are either wilting or derelict in their duties, and that societal decay spirals into a war that sets the stage for even greater tragedies to come - like a thunderstorm before a hurricane.

These once-amazing worlds are coming apart, and need heroes more than ever. And so I’ll begin the actual game review part of this piece with a question first posed by the scholar Gaynor Hopkins:

“Where have all the good men gone, and where are all the gods?”

I’m holding out for a hero ‘til the end of the night

a.k.a.

Talking about ludonarrative dissonance without saying “ludonarrative dissonance”

The inciting incident of SKYRIM’s story is that dragons - extinct for so long that many consider them merely myths - are returning, and threatening the mortal races of the world.

Dragons are innately powerful, magical beings - and at the core of their power is their language. Dragon language makes will into reality. For instance: When they breathe fire, they are simply uttering the word for "fire" in their tongue - and to speak it, is to make it real.

For dragons, this power comes naturally from their immortal souls. When a dragon dies, it can be resurrected by another dragon speaking the proper words. This means the dragon threat can’t be beaten conventionally, because they can just keep coming back.

Mortals can learn the dragon language, too - they call it “the Voice” - however, it takes a lifetime of devout, dedicated study. It takes many long years to master even a single phrase in the Voice.

The only living masters of it are a monastic group of elders called the Greybeards, who live in seclusion atop the highest mountain in the continent. When you go there and meet them, most of them say nothing but to simply whisper your name in the Voice - and even that whisper is so powerful that the castle you are standing in shudders when they speak it. Such is the power of the Voice.

So, who are you?

You are a fated hero called the Dragonborn - a mortal with a dragon’s soul. As a result, you are able to learn, master, and use the Voice effortlessly, as if it were your native tongue - without the long years of study. Additionally, when you kill a dragon, you consume its otherwise immortal soul. This ends the dragon’s existence permanently, and increases your mastery over the Voice, giving you access to more powerful phrases. Thus, you are fated to be the answer to the existential threat of the game: You are the only being who can not only match the might of the dragons, but also halt their otherwise endless onslaught.

The main villain is Alduin, who is the first and mightiest of the dragons - and he is, in an interesting way, your mirror. Just as you alone possess the ability to consume the souls of dragons, Alduin alone possesses the ability to go to the afterlives of mortals and consume their souls to restore his own vitality. So not only does Alduin threaten the mortal world, he also threatens the entire spiritual order of existence.

And the Voice is key to beating Alduin. You find out that in the past, the very first group of dragonslayers did something thought to be impossible - they invented a new phrase in the Voice; a phrase that expressed the experience of mortality - which is both alien and anathema to dragons. Poetically, this phrase granted them the power to force dragons down from the sky, allowing dragonslayers to attack them. But in order to learn the phrase, you must take its essence into your being, and that essence is hatred of dragons - you must poison your soul with this malice, in order to wield what may be the world’s only salvation. The Greybeards don’t want you to do this, because they think mortal concerns (like survival) are ultimately not as important as the transcendent pursuit of enlightenment - after all, the world has to end some day.

I’m going into this much detail about the basic set-up of SKYRIM both because I want to give it the fairest shake possible, and because I want to highlight that there is some genuinely cool and thoughtful stuff going on here. The idea that learning a phrase can irreversibly change you is simultaneously fantastical and rooted in the real-world concept of linguistic relativity (sometimes called the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis) - i.e. the concept that your cognition and worldview are shaped by the limits of your language. Hell, the basic concept of the Voice is basically linguistic relativity taken to a magical extreme - your language doesn’t just shape how you see the world, it shapes the world itself.

An ancient wall carving in SKYRIM details the tyranny of dragons in ages past, and how legendary heroes twisted the dragons’ own language to rise up against them

This is some cool shit!

It would be neat if the game were about it - but it's actually not.

Lemme now walk you through how you actually play SKYRIM.

You begin the game as a nobody, with no special skills or personality whatsoever. You become stronger by leveling up, and the way you do that in SKYRIM has nothing to do with dragons or the Voice or any of that. You improve your skills - whether mundane or magical - just by doing them, over and over again. For example, you get better at crafting weapons and armor by smithing things in a forge. These are things that anyone in the world of the game can do, so what the game’s mechanics are teaching you is that the only reason why you are so lethal in combat or able to withstand dragonfire or whatever is because you are the only person on the continent who bothered to craft hundreds of iron daggers in a row. (At least, until they patched that out. Now, you have to craft hundreds of iron daggers and then hundreds of necklaces to be able to max out your smithing skill. Immersion!)

“So what,” you ask, helpfully setting up a transition to my next point, “Isn’t this basically how RPGs work in general - starting out on the bottom and then leveling up until you are powerful?”

The big problem here isn't that you start on the bottom - it's that the way you actually play the game undercuts and contradicts the story elements that the game is supposed to be all about.

For example, the dragon phrases (called "shouts") that you wield - they’re central to the game’s story, they’re required to beat the final boss, and they’re the one thing that you can do which (almost) no other character in the game can do. But a majority of them are either so narrow in their use, or eclipsed by other options (e.g. the fire breath shout gets outshone by fire magic), that most gameplay doesn’t center on them at all. They also have a cooldown period before you can use them again - so even when you are using genuinely useful shouts in combat, you only end up using them once or twice at most.

Outside of that, the game actively discourages using the thing that is supposed to make you special a whole lot of the time:

It’s difficult to control what your shout hits, and if your combat shout accidentally hits a friendly character, they might become hostile (or just die) - so you often want to avoid using them in fights where you have allies.

If you use a shout in a town or city, a guard will approach you and force you into dialog where they tell you not to do it again or else they might fine you (or worse). Yeah, they fine you for using your unique heroic ability.

And, of course, the way you improve your own shouts is by consuming the souls of dragons. Which means you have to kill dragons. Which means primarily relying on other skills, like melee weapons or archery or magic. So even trying to focus on shouts requires you to be good at alternatives to shouts.

How many games have you played where the game repeatedly tells you not to use its featured mechanic?

One shout is called “Throw Voice”; it creates a distracting sound in the distance that lures enemies toward it. For most of my main playthrough of the game, I never found a use for it. Then, finally, I was in a quest where I needed to sneak into someone’s chambers while guards patrolled the hallways. Perfect! I hid around a corner from the hallway where the guards were, and used the shout to create a sound in another room.

The nearest guard then made a beeline to me, in my hiding space, and initiated the “please stop shouting” dialog. After I said “won’t happen again”, the guard then returned to their hallway, and resumed their patrol as though they had never seen me.

What the fuck, SKYRIM?

Oh and remember the Greybeards, who showed you that even a whisper of the Voice could shake an entire castle? Yeah, shouts don't work like that anywhere in the game. You shout left and right and never shake any castles or anything like that, even when using the shout called “Unrelenting Force”. That was just a straight-up lie.

There are also a couple of shouts that are used only because the game requires you to use them. For example, “Clear Skies” is a shout that disperses the weather - which has no mechanical impact on gameplay whatsoever outside of two situations in the main questline where you are forced to use it to progress. (Hilariously, there’s also a place in the game that was coded to be snowy all the time, not for any particular reason, and “Clear Skies” doesn’t work there.) When the game includes multiple shouts like this, whose only function is to get past a plot-gate, it is telling you something about how to think about shouts. It’s telling you there that the only reason they’re important is because we said so.

Having some mechanics like that isn’t necessarily a game crime - but when you represent the core concept behind your game’s story that way, well, it’s not good for how the player relates to that story.

On the one hand, you have characters telling you about lore that makes you a fated hero burdened with the fate of the world.

And on the other hand, the experience of playing the game itself is telling you this lore is just a stamp on the back of your hand so you can be allowed past the velvet rope in the plot.

He’s gotta be strong and he’s gotta be fast

Now let’s give WITCHER 3 the same treatment we just gave SKYRIM: We’ll start out with the lore behind the game’s hero, and then see how it bears out in gameplay.

Unlike SKYRIM, the protagonist of WITCHER 3 is a pre-established character: Geralt of Rivia. And what you need to know about Geralt is that he is a witcher.

Witchers are a social caste of monster hunters. They are made from orphaned children, who are then subjected to a torturous battery of chemical and magical procedures that leaves their body forever transformed. 70% of children don’t survive this process. Those that do, are then further traumatized by an entire childhood spent doing nothing by studying and training to kill monsters, spending all of their formative years on increasingly lethal trials in isolation from the rest of society.

The people that make it through all that become superhuman. They have keener senses (including the literal eyes of a cat), which combine with their wildlife studies to make them peerless trackers. They have heightened reflexes, which combine with their years of combat training to make them singularly dangerous fighters. They are unnaturally resilient, which grants them a tolerance to toxins that would kill ordinary people and a lifespan several times that of a normal man. These changes are not without their costs - in addition to the cruelty one has to endure to become one, all witchers are sterile, their bodies are susceptible to further mutation, and they are said to have lost their capacity for emotion. (In my head-canon, the last bit isn’t true - the behavior that people think is indicative of a “lack of emotion” is instead due to witchers being profoundly traumatized, isolated, and ostracized for a length of time that almost no-one else alive has experienced.) And since their life’s trade is necessarily unpleasant, no matter how necessary, they are often treated little better than the monsters they are hired to kill.

By the time WITCHER 3 takes place, witchers are even rarer than normal; with no new witchers having been made for several decades, the tradition seems likely to die out.

Geralt of Rivia is a particularly famous and accomplished witcher who is already several hundred years old. He’s the kinda badass who can fight blindfolded while balancing on a pole, who knows enough about monster ecology and anatomy to brew toxic potions from their remains to help hunt other monsters, whose knowledge of forensics allows him to figure out how a fight played out days before he arrived at the scene.

That’s where you begin the game in WITCHER 3.

A young child performs stupendous feats of agility during training to be a witcher, while Geralt - already an accomplished witcher - harshly criticizes their form and technique

This is also cool, but by itself it doesn’t necessarily count for a whole lot. I clearly think all this witcher lore is pretty rad (enough to make my own head-canons), but I have to admit that this is basically just a fantasy version of the HALO guy’s backstory (cue Don LaFontaine voice: “In a world…where stereotypically masculine traits…get exaggerated until they make you a superhero…but also you’re kinda sad about it…”). It’s fine, but I can’t say it’s more innovative than “what if dragons ruled the world because they represented a magical reductio ad absurdum of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis?”. As with SKYRIM, our focus here is deeper than that: How is this premise represented by the gameplay?

I talked about leveling up in SKYRIM, so let’s talk about leveling up here.

In WITCHER 3, you level up from fighting monsters and completing quests. This is already an improvement over SKYRIM’s approach, because it encourages diverse activities rather than repeating the same ones in bulk - but I want to point out something else, something seemingly superficial: how your level-up screen is represented to the player. The “flavor” of the leveling-up interface is that you are promoting the physiological mutations that you have as a witcher. This means that you are enhancing attributes that normal people don’t have, in a way that only witchers can do.

By contrast, in SKYRIM there is no in-world explanation for your level-up interface - which, fair enough, most people won't care or notice; leveling up is leveling up, and the rest is just window dressing, right? Sure, to an extent, but even this superficial design decision constantly reinforces a core element of the game’s fiction. The fundamental reason why the player is better than everyone else in gameplay terms is directly tied to what makes the character they are playing as exceptional in story terms. And when even the interfaces make this explicit, that embeds the concept deeper into your overall experience.

Now let’s step out of the menu screens, and look at how the concept of being a witcher is communicated during other parts of gameplay.

A lot of your time in WITCHER 3 is spent hunting monsters. Most of these quests progress pretty similarly. You’re hired because some creature attacked a merchant cart or carried away some villagers or something. First, you interrogate the witnesses to gather basic information and clues. Then, you go to the “scene of the crime”, and examine the evidence there - often revealing new wrinkles in the initial story. These examinations are usually done using your witcher senses, and therefore are implied to be things that normal people couldn’t notice.

Again, that’s already better than SKYRIM, but what I really love is this: Each time you examine a blood splatter or corpse or footprint, you are treated to a piece of voice-acted dialog that is unique to that piece of evidence in that quest, which explains what Geralt learned from it. These are things that Geralt knows because of his study and experience as a witcher - things like:

There’s a lot of weak monsters in the vicinity - which means the beast isn’t attacking other monsters, which means it isn’t territorial, which excludes some possibilities for what the beast might be

Most of the wounds on the victim didn’t bleed much, which means they were made after the victim’s death - so they were likely made by scavengers, and not whatever killed the victim

The footprints you’re following are both deep and uneven, which suggests not just running but panic, and therefore that the attacking creature surprised its quarry

Where a body is found relative to the likely lair of a monster suggests how far the monster was able to carry it - which in turn suggests how old the monster might be, and thus its behavior

This is all well-written and well-performed, but what makes me love it is that each of these (again, unique) lines teaches you about Geralt and about the world of the game, in a way that’s reinforced through gameplay. Unlike how dragon shouts get reduced to the status of progress-gating gimmicks or incidental combat options, Geralt’s knowledge and proficiencies as a witcher are foregrounded constantly as you play. Hunting monsters requires preparation, investigation, and tracking.

Geralt narrates his examination of a dead griffin, as part of his investigation into why another griffin in the area is behaving oddly

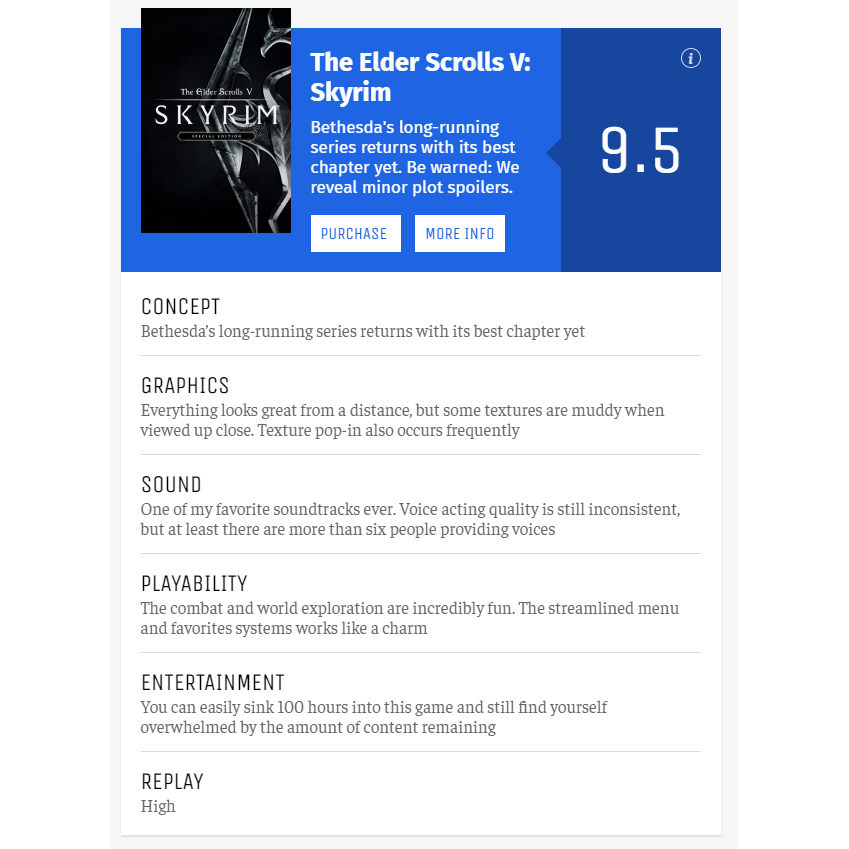

I have to make some clear here: It’s not just that these examples of mechanics and writing from WITCHER 3 are individually better than their counterparts in SKYRIM; it’s that the mechanical representation of the game’s narrative elements (i.e. the Voice, or being a monster hunter) through gameplay matches the story that’s supposed to be taking place. Like I said at the top, it’s still very common to talk about the elements of a video game as though they were totally separate pieces that don’t interconnect. You can see this reflected in the way that video games used to be reviewed, breaking down ratings into component scores for things like “graphics” and “gameplay” - which is closer to how we review shoes than, say, movies.

The compartmentalized review score given to SKYRIM, as archived before IGN switched to only assigning one overall score for their reviews

Unlike many other game review sites these days, Game Informer still gives video games these sorts of compartmentalized scores

Like with movies, the different crafts involved in making a game (writing, interface design, mechanics, combat structure, etc.) impact each other’s effectiveness. This is why I’m approaching the question of “Which game’s story is better?” through their mechanics, rather than just trying to figure out whether one series of quests was more annoying than the other, or whether dragons are more interesting than superhuman mercenaries.

The punchline here isn’t that the basic premise for WITCHER 3 is better than SKYRIM, or that its mechanics are more fun - it’s that these elements are more harmonious with each other in WITCHER 3 than they are in SKYRIM, and the result of that interplay is more compelling as an overall experience. In WITCHER 3, I’m supposed to be a badass monster hunter, and other parts of the game - from menus to mechanics - agree. In SKYRIM, I’m supposed to be the Dragonborn, a hero whose unique might and destiny arise from their access to a magical Voice that can shape the world - but that’s not what playing the game suggests. Only two questlines (three, if you count the expansions) even have dialog that refers to me as the Dragonborn at all.

Again, things like menu screens and incidental voice lines may seem like a little things - and to some extent they are - but they nonetheless contribute to how you parse the whole game, to whether the world feels real or fake. This is part of why, like I said at the start of the series, WITCHER 3 just embarrasses SKYRIM - because SKYRIM doesn’t even get these little things right.

So.

Uh.

What about the bigger things?

And he’s gotta be fresh from the fight

As you might’ve noticed from the screenshots above, most reviews for SKYRIM are downright exultant. This makes it really interesting to read those reviews after you’ve actually played the game for a long time. It’s a little like visiting a house for sale where you know bodies are buried in the walls, and listening to how the real estate agent tries to sell it to you - you spend the whole time trying to figure out if they’re glossing over smell of rotting corpses, or if they genuinely don’t notice.

In this metaphor, one of those corpses is SKYRIM’s combat system.

One review breathlessly praises how simple the combat system is, because you can put any weapon or spell in either of your hands and just press a button to do it, which is certainly true.

Another review described combat as “largely a test of skill”, in the same sentence where they admit enemies often have trouble getting around tables, which is just a fascinating claim.

Yet another review begins by acknowledging that SKYRIM “hasn’t got the best narrative of any RPG, the best combat, the best magic system or even the best graphics” - no argument from me so far - “but it does have one of the biggest, richest and most completely immersive worlds you’ve ever seen”. (We’ll get to that claim in the next and final piece in this series.)

But over the past decade of reviews (and re-releases onto new platforms, which means more reviews that should theoretically have the benefit of hindsight), I think Mike Krahulik - the artist of Penny Arcade - put it best, on the day SKYRIM was first released:

“There’s just nothing to the combat. [...] Fighting shit in SKYRIM isn’t about how well you can manipulate your controller, it’s about numbers. The level of your shit versus the level of whatever you’re pointing your hands at.”

And yeah, that’s really pretty much it.

As indicated above, you can map a weapon or spell to either hand, and press the button associated with that hand to use it. There are no real evasion options (backing up is slower than walking forward, which means pursuing enemies can always catch you if you’re still trying to fight them while fleeing). Combat therefore reduces to a contest of numbers: are you doing more damage per second (relative to your health) than your enemy is? Then you win!

No matter how many theoretically different ways you have to deal damage in the game, one of them will produce the biggest numbers, you will map that to your dominant hand, and combat will consist almost entirely of simply pressing that button while facing your enemy.

That, and shooting arrows at enemies that can’t find you.

Many SKYRIM players joke about how “everyone ends up playing stealth archer” (i.e. plinking enemies with arrows while hiding). That’s not so much a “different way to play” as much as it is the logical conclusion to the way combat works: you can out-damage your enemy if they just can’t hit you because their AI was built full of holes big enough for you to hide in. I once spent close to a half hour “stealth archering” a cave full of higher-level vampires to death. I would donk one in the head with an arrow, causing it to bark “What was that??”, search ineffectually for me for a minute or so, say “It must’ve been my imagination”, and then go back to standing in place.

See, the reason why “everyone ends up playing stealth archer” is because that’s basically the only way you can punch up - you’re guaranteed to lose any fair fight against a sufficiently stronger enemy. (That, and pausing the game to chug healing items mid-combat so that you can win fights that you otherwise wouldn’t survive.) It’s not some weird quirk that we all end up trying out this playstyle. The way combat works in this game funnels you into it, whether it’s your first playthrough or your 27th.

Almost every area in the game is available at the outset, so it’s likely that a new player encounters some enemies that they just can’t beat any other way, and they inevitably realize that all the incentives are pointing to this incredibly dumb way to play. On my first playthrough, I beat a dangerous undead dragon-priest that was way stronger than me, just because it got stuck on a rock and I happened to have a couple hundred arrows in my inventory. It took forever.

This isn’t just a low-level strategy, by the way. It gets even better if you keep investing in it, trivializing most of the fights in the game - whether you’re against wizards or mammoths or ancient dragons.

For example: If you level up enough, you can gain the ability to basically turn invisible just by crouching, which is exactly as silly as it sounds:

Combat is the most mechanically complex task a player can do in SKYRIM. It’s what most players will spend most of their time (other than moving from place to place) doing. And it’s also the main obstacle the game places in front of your progression. Yet if someone tells me they’re “good at SKYRIM”, I have no clue what they mean.

If someone tells me they’re good at WITCHER 3, though, I have a very clear idea what that means.

I won't go over the entire combat system of WITCHER 3, but just to paint a picture of how much more depth there is to it:

You have a variety of evasive and defensive options (dodging, rolling, parrying, magic shields), and enemies have a variety of offensive options that you can respond to if you learn how they telegraph their intentions and are quick enough to react

Both Geralt and his enemies take different amount of damage when attacked from different angles, making positioning more strategic than just “can we hit each other”

Different enemies have vastly different behaviors, and thus require different approaches to effectively overcome - rewarding the player for learning at least some variety in approaches to combat

There are additional combat systems (like the “adrenaline point” system) to provide different incentives for how to approach building your version of Geralt

So what's the punchline here? Yeah, combat is different in each game, but what does that amount to?

For one thing, combat in WITCHER 3 rewards players for proficiency with the physical mechanics of the game. For example: You can get good enough with combat that you consistently beat baddies that could take you down in just one hit. It doesn't require celebrity-streamer-level skillz, either. I did this a lot in my first run of WITCHER 3. (Don’t do that, by the way - I was just trying to play the game like it was DARK SOULS, because I really like DARK SOULS.) By giving you a variety of ways to avoid damage and interact with the enemy, you can get proficient enough at fighting that you can tango with things way above your weight class.

This is a good thing for games: It lets you develop and exercise mastery.

It means the game has room for you to get really good at it, which is strong intrinsic motivator (it’s enjoyable to get better at things). By contrast, SKYRIM’s explicitly repetition-based leveling-up system, which entirely determines your efficacy and longevity in combat, only rewards you for hours spent playing.

Is that inherently bad?

Well, no, not inherently. I mean, it’s basically how every main-series Pokémon game works: You pick your starting critter, it gets stronger just by fighting over and over, and then you beat the last opponent and you’ve won. Just like in SKYRIM, if an opponent is a much higher level than you’re intended to fight, there’s basically no way you can win. These features aren’t unique to SKYRIM.

But you know that half-joking observation that everyone makes about each Pokémon game? How it’s pretty silly that you always play as an 11-year-old who gets their very first Pokémon, and then like a week later has taken down massive criminal organizations and beaten the very best Pokémon trainers in the world?

You know how Pokémon games never pride themselves on story the way SKYRIM does?

The stories in Pokémon games exist in a setting where appliances and livestock can be your best friends, where everything is cute, and where the most powerful force is the bond between a kid and their magical super-pet. Becoming the best in the world just because you spent enough time with your favorite pet doesn’t undermine the basic premise of Pokémon - it is the basic premise of Pokémon.

SKYRIM is the fifth main entry in the Elder Scrolls series. Each game tells its own story in the same expansive fictional world, and they all explicitly and concretely tie together. There is a documented history of empires and apocalypses and heroes throughout Elder Scrolls, and it’s cumulative. The guy who founded an empire in one game ascended to godhood - centuries later, that same empire lost a war against an enemy that then banned worship of this new god, and that ban is the pretext for the war that sets the backdrop of SKYRIM. All these sorts of things are very much what Elder Scrolls games want to be about.

So when the gameplay isn’t about that, it’s a bigger problem.

SKYRIM (and virtually every other title released by Bethesda Game Studios) is almost single-mindedly about exploration. You explore, you kill enemies, you loot, repeat. The combat is part of that loop, but only in an obligatory and unmotivated way. At best, it makes you feel powerful, but it's never really engaging - combat is just something to do. It reinforces the core loop by indicating that you’ve found something new (because there are new things to kill), while making itself so streamlined that it gets out of your way as fast as possible.

The major systems in SKYRIM just don’t work together. It wants to tell this big, Tolkien-esque saga with several encyclopedias’ worth of backstory and setting (or at least, it wants you to think that) - but it doesn’t actually tell you that story. This is the sort of thing that media critic and video essayist Hbomberguy calls “theoretically interesting”: it wants to take credit for all the material, but it doesn’t successfully relay it within the media itself. At some point, you don’t get credit for what your story could have been like based on all the lore and shit that went into it - you have to actually tell your story well.

And not only does the gameplay in SKYRIM not tell you the story that the game is trying to tell you - it isn’t very satisfying an experience either.

It might look really cool and the controls might be very simple and intuitive, but all that’s going on here is Bethesda figured out how to hijack the dopamine pathways in my brain with minimal effort. Mechanically, the majority of gameplay is about combat - but since combat just comes down to repetition and big numbers are all that matter, most of the stuff you end up discovering ends up not mattering. You’re excited to find it, and then you put it in your favorite drawer in the house you built yourself (if you bought the Hearthfire expansion) that you never spend time in, and look for the next thing.

When playing WITCHER 3, I found myself exploring new areas in order to find contracts to hunt monsters - because hunting monsters was fun. Instead of chasing the dopamine hit that comes with the “you discovered a new location” sound effect and then promptly moving on, I was chasing more opportunities to engage in WITCHER 3’s mechanics - because the gameplay was fun, because I could get good at it, and because it made me feel what the story was trying to tell me (most of the time, at least).