Silent Hill, Pennsylvania

It’s April, 2006.

I’m trying to transfer into film school, and the Silent Hill movie is about to drop.

I’ve just come out of this weird pocket dimension where my sleep schedule was upside-down for a couple weeks while I binged SILENT HILL 4 and wrote stories about being trapped in my own mind instead of stopping myself from failing classes.

I feel like I am simultaneously living my worst life and my best life. And I am super fucking pumped for this horror movie coming out about the games I am currently obsessed with.

For the past few months, I’ve been following the movie’s official blog, where director Christophe Gans extolls all the right things about the games (he even loves SILENT HILL 4 as much as I do!), thoughtfully answers fan questions about his approach to adaptation, and just generally says dope shit like “It is the responsibility of every horror movie to ask questions about society”. This guy gets it. I am on board. Shit’s gonna be awesome.

The movie drops.

It is not what I was hoping for.

It is really, really not what I was hoping for.

For a while, I try to salvage my prior hype. I tell myself that it’s still a good movie, if you can just step around the bad parts. I still buy the DVD when it comes out.

But as time goes on, my feelings about SILENT HILL the movie only grow dimmer. The bad parts crowd out my other memories. A sequel - SILENT HILL: REVELATION - comes out in 2012, and it’s even worse (though worth a watch, if you want to see a pre-GAME OF THRONES Kit Harrington stuck in a comically bad role), which further cements my contempt for Silent Hill’s film legacy.

It’s January, 2022.

I’m chatting with a friend who’s also into horror movies. Our tastes diverge pretty significantly, but his takes on media are always extremely well-considered, and I greatly respect his insights.

He tells me he just saw SILENT HILL for the first time, and just as I’m getting ready to start dunking, he says he mostly enjoyed it. The main bad thing he has to say about it was that it was too long - a critique which had never made it onto my own lengthy list of grievances about this movie that I’d spent 15 years building.

This throws me for a loop, but not nearly as much as the next thing he hits me with:

It’s hard to overstate the amount of psychic damage this message inflicted upon me.

SILENT HILL is a 2006 major motion picture that, to me, had become synonymous with disappointment - a clumsy, facile thing dressed up as something I wanted to love. It’s vapid and plastic and cashing in on a brand.

NIGHT IN THE WOODS is a 2017 indie video game launched from a Kickstarter campaign with a funding goal of 0.1% of SILENT HILL’s budget, that I utterly adored for its intimate character portraits and achingly soulful depiction of a specific slice of American culture. It’s clever and authentic and original.

And yet.

And yet.

My buddy’s right. There is something of NIGHT IN THE WOODS in SILENT HILL.

Since getting that message, I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it. I’m rethinking how I’ve been looking at and talking about every movie I’ve seen in the last few years. I’m returning to a place I thought had died inside me a long time ago.

And you’re coming with me.

Spoiler warning

The rest of this article will discuss endings and major narrative elements for both NIGHT IN THE WOODS and SILENT HILL (as well as the game the movie was based on).

NIGHT IN THE WOODS is particularly good, and discovery is a big part of the experience. Starting right in the next section, I’m going to reveal things that aren’t just “stuff you don’t learn until later”, but specifically the answers to questions that drive a lot of the game.

If you’re interested in the game at all, I strongly recommend playing it first and coming back to this piece later. (According to HowLongToBeat.com, that would take you about 8 hours.)

SILENT HILL…eh, I wouldn’t worry about it if I were you. And the original Silent Hill game is only available on emulators now.

Two dead towns

So, yes: I’m going to be taking a movie that looks like this…

…and comparing it to a video game that looks like this…

…but once you get past that, some similarities do start bubbling up to the surface.

The most basic one is the setting: both SILENT HILL and NIGHT IN THE WOODS take place in derelict towns gripped by a supernatural cult. So let’s start by properly introducing these two pieces of media.

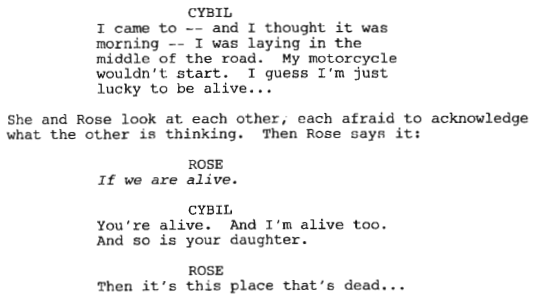

The first Silent Hill game came out in 1999, and tells the story of a quiet lakeside town that has recently suffered a supernatural apocalypse brought about by an esoteric doomsday cult. Seven years ago, the head of the cult (Dahlia) attempted a ritual to create a new god by burning her daughter (Alessa) alive. The ritual failed, and Dahlia has been waging a hidden supernatural war with Alessa since then - one which occasionally plunges the town into a gruesome alternate reality full of monsters created from Alessa’s nightmares. The game’s protagonist is a single father (Harry) who gets caught up in all of this when his daughter gets lost in Silent Hill, and he ends up discovering that she was actually a piece of Alessa’s soul all along. In the canon ending, Dahlia and the supernatural monster she tried to create are defeated, and Harry leaves the town with a new child - now Alessa’s reincarnation - to start a saner life.

Later games in the series (like SILENT HILL 2 and SILENT HILL: HOMECOMING) would dramatically expand the lore, turning the town from the victim of one particular occult event into a more deeply haunted place whose unnatural energies can create horrible realities from anyone’s nightmares - but the movie adaptation mostly sticks to the plot of the first game, i.e. the battle for Alessa’s soul. It does make a few changes, though.

In the 2006 movie, Silent Hill’s cult has a much more specifically Christian bent: instead of trying to create a new god they are mostly focused on burning witches as an act of worship. The cult’s leader is a new character (Christabella), and this time she tried to burn Alessa alive for being a religious pariah. (Dahlia is still Alessa’s mom, but in the movie she gets demoted from villain to victim.) The ritual burning goes wrong, and starts a fire that spreads to the town’s coal mine and forces it to be evacuated. A dark supernatural force offers Alessa revenge, and plunges the town into the same sort of living nightmares as in the game - trapping Christabella’s cult inside. The protagonist is once again a parent whose child goes missing in Silent Hill only to discover that their child is a part of Alessa’s soul, but this time it’s a married mom (Rose). In the finale, Rose helps the supernatural force slaughter the remaining cultists in order to rescue her daughter - but in doing so, that darkness becomes a permanent part of her child. Rose and her daughter leave Silent Hill physically, but remain trapped in a foggy purgatory with just the two of them - Rose having literally sacrificed her whole world for her daughter.

On the surface, SILENT HILL is a relatively straightforward adaptation of its namesake game. It trades occultism for witch-burning, the finale is less about saving a town and more about saving a family, and some characters get shuffled around, but that’s essentially it.

The movie had a respectable budget of $50 million - nowhere near THE AVENGERS levels, but at least double what it cost to make movies like 2018’s A QUIET PLACE or 2017’s IT (adjusted for inflation). The cast is solid. The director is passionate and has a deep understanding of the source material. The special effects are impressive. So what’s wrong with this film?

The biggest problem with SILENT HILL is that the whole cast has barely a single believable human being between them - an impression that’s mostly created by dialog that’s consistently both too goofy and blunt to swallow.

This is most apparent with the cultists, whose lines are so artificial and overloaded with religious language that you can’t picture any of them having a believable conversation about anything. Dahlia in particular speaks almost exclusively in hokey aphorisms, which at best are pithy (“Fire doesn’t cleanse, it blackens”), but more often are just painfully on-the-nose (“They are wolves in the skin of sheep, they brought about their own hell!”).

This is theoretically explained in the fiction by the fact that these people have been squatting in a nightmare dimension cut off from the rest of the world for 30 years (the movie sets Alessa’s burning much farther in the past), so it could make sense that these people are a bit off - except that Rose is so monomaniacally focused on her single objective/personality trait of “find my daughter” that there’s not really much contrast between her behavior and the cultists’. Rose watches the world transform and people get eaten alive by cockroaches with human faces being led by a 12-foot-tall man with a sword, and comes out seemingly unaffected. She’s just as detached from reality as Dahlia.

The end result of all this super-direct, non-naturalistic dialog is that it feels like the movie is shouting its messages at you, which flattens your perception down to just what it’s shouting at you. This makes SILENT HILL come across as just a particularly dumb morality play. Right before the climax, Rose goes up to a bunch of religious fanatics who have literally just finished burning someone alive and shouts “Your faith brings death!” like it’s this big exposé, and you sit there thinking “Is that really all this was building up to? Telling us that burning witches is bad?”

The very end of the movie is one of the few moments where it uses cinematic language alone, without hitting you over the head with dialog, and as a result it comes across as more opaque than it really should. The first time I saw Rose and her daughter remain trapped in that foggy purgatory after dealing with the cultists, I was confused (“Wait, so was Alessa actually an evil witch all along?”), because the movie had trained me to expect its themes to be delivered strictly through obvious dialog - but there wasn’t any in the final moments.

And then eventually I remembered that the ending was explained through obvious dialog, just earlier, when Dahlia had told Rose “Evil wakes in vengeance; be careful what you choose!”

So that’s SILENT HILL.

What’s going on with our other freaky town?

NIGHT IN THE WOODS is the story of Mae, a 20-year-old who drops out of college and returns to her old stomping grounds to try and figure her life out. Mae’s hometown, Possum Springs, has been slowly falling apart ever since the coal mine and glass factory closed down. With jobs evaporating and each subsequent generation fleeing (if they can), Possum Springs is reduced to husks and memories. As Mae reconnects with her old friends and grapples with how much her world is changing, she stumbles into a mystery surrounding a string of disappearances in Possum Springs. It turns out that some of its residents discovered an ancient supernatural force in the old coal mine, and began kidnapping people to sacrifice to this being in the hopes of restoring prosperity to Possum Springs. After confronting the cult in their underground sanctum, Mae faces the darkness that felt like it was slowly crushing her entire world, and makes the deliberate choice to hope for something better.

Even as I spoil major elements of NIGHT IN THE WOODS’ story, I find myself still wanting to hold a lot back. Mae’s journey is really worth experiencing in all the game’s painfully human detail.

Part of why my friend’s comments threw me so hard is that one of NIGHT IN THE WOODS’ biggest strengths is exactly SILENT HILL’s biggest failing: its characters. NIGHT IN THE WOODS is overflowing with rich, interesting, real characters.

Part of this just comes from the difference in medium. SILENT HILL has a relatively large amount of lore and conceptual set-up for a movie (even a 2-hour one), which leaves little time to get to know all the different characters on any level deeper than “what they are currently trying to do”. The 8-ish-hour playtime of NIGHT IN THE WOODS, however, provides a lot more room to show off each character’s personality and idiosyncrasies. Movies can’t really do the sort of exposition-via-exploration that games can.

On top of that, aimless exploration is specifically a big part of NIGHT IN THE WOODS. In a really effective recreation of what it’s like to be a recent dropout unsure of what they want beyond “to feel connected again”, most of the game amounts to wandering around and hanging out with your friends. For the first half of it, characterization is the story of NIGHT IN THE WOODS - and there’s nothing approaching the urgency of “save your daughter from a haunted town full of monsters” until the very end. Until then, you just poke around and see what you can find.

Despite these differences in narrative constraints, though, NIGHT IN THE WOODS still achieves a lot more with what it has than SILENT HILL does, and again a lot of it comes down to dialog (which accounts for nearly all of the text in NIGHT IN THE WOODS).

The game’s simplified art style means that lots of its characterization relies on the actual words being said. At the same time, these visuals also heighten the effect of the dialog: the contrast between colorful talking cartoon animals and the painfully down-to-earth things they are saying makes those things seem even more real.

And fuck, it gets pretty goddamn real - way more than the glimpse I’m showing here.

None of this is to say that the artwork for NIGHT IN THE WOODS isn’t expressive by itself, from the way Gregg’s arms flail excitedly to the way Bea’s cigarette seems to hang off her lip. Possum Springs itself is full of detail too, from the weathered murals and statues throughout the town to the barely-legible sign reading “Thank you for 28 wonderful years” in the door of a closed-down family restaurant.

And these images bring us back to what NIGHT IN THE WOODS has in common with SILENT HILL: the towns they take place in.

I know that corpse

My friend had said that both NIGHT IN THE WOODS and SILENT HILL were set in post-industrial Pennsylvania. This is, essentially, correct - but it takes a couple steps to get there.

For NIGHT IN THE WOODS, it’s simple: Possum Springs is just straight-up set in Rust Belt Pennsylvania, as is strongly hinted in the game itself (including the lengthy and detailed history of the town) and further confirmed by creators Scott Benson and Bethany Hockenberry.

Silent Hill, on the other hand, has been a bit more mobile.

In the first game, Silent Hill was set somewhere in New England - with fans eventually determining that it was specifically in Maine, near Portland (a fact which got canonized by the later games in the series). The first game was packed to the gills with references to American horror media, so it’s likely that Silent Hill’s placement was a reference to and/or inspired by horror novelist Stephen King, who was born in Portland and frequently set his stories in sleepy, creepy Maine.

When the movie began production, the script had placed Silent Hill in the Bible Belt. In that draft of the script, Rose was from Chicago, and got lost in Silent Hill when she was trying to drive her daughter to a faith healer in Louisiana.

At some point during production, Silent Hill got moved to West Virginia. The searching-for-a-faith-healer plot had been changed (now, Rose was looking to take her daughter directly to Silent Hill, because her daughter was screaming the town’s name while sleepwalking) - so the decision was probably made to place Silent Hill closer to the real-life inspiration for the movie’s version of the town: Centralia, Pennsylvania. (On the movie’s official blog, Director Christophe Gans said they couldn’t place Silent Hill in Pennsylvania itself “for legal reasons”.)

And basing this version of Silent Hill on Centralia is secretly one of the most interesting things about the film adaptation.

Centralia in 2001, around the time that SILENT HILL was being pitched. Photo by Peter R. Rekus

Centralia is one of America’s most famous ghost towns (especially after the release of SILENT HILL, which heavily publicized its inspiration).

The borough was officially incorporated in 1866, a decade after the first two coal mines in the area were opened. Centralia was built for and around these coal mines, and its population never cracked 2,800. As coal companies left (beginning with the start of the Great Depression in 1929 and ending with the last mines closing in the 1960s), residents took to bootleg mining - stripping and scavenging what they could from the old tunnels. In 1966, the same year as the town celebrated its centennial, the railway stopped running to Centralia. The town’s prime was already past it, and the tide was receding.

Centralia in 1966. Photo copyright Dan Callister/Shutterstock

But none of that is why Centralia is famous.

In 1962, a trash fire in an old strip mine pit managed to spread to the forsaken mine network. Igniting the vast underground spiderweb of coal seams that was the town’s reason for existing, the fire swiftly outraced initial efforts to contain it. It’s been burning nonstop since then, and there’s enough fuel for it to burn another 200 years. Fire had become a permanent resident of Centralia.

For years, people just lived on top of the inferno. Some residents enjoyed not having to shovel snow in the winter anymore. But the longer Centralia burned, the more dangerous it got. Streets began to crack. Fainting spells caused by noxious fumes became more common.

In 1979, gas station owner (and then-mayor) John Coddington went to check the temperature in one of his underground tanks and discovered the gasoline was boiling.

In 1981, 12-year-old Todd Dombowski nearly died when a sinkhole opened up directly underneath his feet in his grandmother’s backyard (he managed to grab a tree root to stop his otherwise lethal fall into the pit of steaming carbon monoxide).

These incidents capped off years of reporting on the dangers of the fire by investigative journalist David DeKok, and major relocation efforts began shortly afterwards.

Handmade street signs for Centralia’s final residents, from 2013. Photo by Dan Gleiter

Some residents refused to leave, despite the sinkholes and fissures spewing toxic fumes that had taken over their town. In 1992, with about 63 residents remaining, the governor condemned the entire borough. In 2002, with about 21 residents left, the Postal Service stripped Centralia of its ZIP code. In 2013, state officials reached an agreement to allow Centralia’s last 7 inhabitants to live in their homes until their deaths, at which point the last houses in Centralia will be demolished. As of this writing, there are still five people living in this now-famous ghost town, with empty lots and steaming earth for neighbors.

Aerial view of Centralia in 2009 - all that remains are the roads, house-shaped patches of differently-colored grass, and fewer than a handful buildings. Photo by Flickr user tconrad2001, who notes: “My Great Grandfather's brother is buried in the cemetery there. He died in a mine accident at age 40 in 1909 and left a wife and 6 kids.”

A faded sticker, pleading to no-one, on the door of Centralia’s old municipal building in 2018. Photo by Owen Amos

It was Canadian-American screenwriter Roger Avary, whose father was a mining engineer, that brought Centralia into SILENT HILL. Avary stitched Centralia’s mine fire and small-town collapse into the film’s version of Silent Hill, a change which was enthusiastically approved by Christophe Gans (who had also written the initial treatment for the film) and Akira Yamaoka (representing the original Japanese team behind the games). The movie even adopted “Centralia” as its working title.

Whereas the Silent Hill of the games was (initially) a more generic haunted town, Avary’s vision was far more specific. In a draft of the script from October 2004 (around the time that Avary said he “finished the SILENT HILL script” for the first time), Rose would’ve driven through a neighboring town in a scene that more clearly establishes this picture of wilting Americana.

Although the town from this scene was an old farming community rather than a mining town, it tells a similar story. Both types of town were birthed by an industry that abandoned them, scavenged by big box stores and other chain establishments, and ultimately left to bleed out just the same.

Silent Hill’s location in the movie was able to hop around partly because this type of town-rot is recognizable in so many places throughout North America. Shots of Silent Hill’s abandoned streets were filmed in Brantford, Ontario - where there were already blocks of vacant, run-down storefronts. As the location manager for the film put it: “Here, half of our work is already done.”

But it isn’t just the mundane, physical aspects of Silent Hill that get enriched by importing Centralia’s history - the supernatural elements take on new meaning, too.

The defining motif of Silent Hill as a setting is that it shifts between different versions of itself, one of which is a dark mirror of reality. In all the games up to the release of the movie, the nightmarish version of Silent Hill had a fairly consistent visual language of architecture blurred with anatomy - a sunless world of reds, oranges, and browns; where blood and rust are omnipresent and indistinguishable from one another. It’s important to point out that when Silent Hill transforms into this version, it doesn’t simply become gorier - it also becomes more industrial: plaster walls turn into chain-link fences, door knobs become heavy metal valves, floorboards become rusted pipes.

The “otherworld” version of a school in the 1999 game…

…and in the 2006 movie.

In the context of the games before the movie, these distinctive aesthetics convey a general sense of harshness and intimacy, of an internal truth being gruesomely laid bare. In the context of a former mining town, however, this architecture of steel and sinew looks much more like the literal corpse of industry. The movie’s decision to set the occult tragedy that dooms Silent Hill in the 1970s (as opposed to the 1990s, in the games) lines it up with the closing of mines and factories that trapped generations in the carcasses of these towns.

And, fascinatingly, it’s the villains of both SILENT HILL and NIGHT IN THE WOODS that think they’re saving these dead towns - the heroes are just normal people trying to live.

This is made explicit in NIGHT IN THE WOODS: the cult of Possum Springs believes that the chthonic being living deep under their town will halt the exodus of jobs and talent from Possum Springs, while simultaneously sealing the town off from any other transformative influences like government programs and new immigrant populations. In exchange, the cultists have to keep this dark thing fed - which, of course, means murdering the people that the cultists already thought of as “undesirables”: the unhoused, victims of substance addiction, and - increasingly - young adults and children that they think are growing in the wrong direction, who would either leave the town or “amount to nothing” (as determined by the cultists).

These cultists are never fully identified, instead remaining in the shadows and claiming to Mae that they could be anyone she meets in the town. It’s a great execution of the “horrific conspiracy in a quiet community” trope, but there’s another reason why the villains aren’t revealed: it doesn’t matter. Whether or not the members of the town council who ask cops to “round up any dirtbag teens or vagrants that’ve been hanging around town” for vandalizing an old mural in a flooded trolley tunnel are literally members of a death cult or not, they are functionally the same already.

The cult in the film version of SILENT HILL is similarly obsessed with tradition. Although they are described as “witch hunters”, their ritualized murders aren’t just punitive - they seem to be offerings, too. When Christabella burned Alessa alive in the 1970s, she jubilantly called it a sacrifice - and went on to exult that these sacrifices gave the community its unity, as well as its “purity”. These aren’t rare and unpleasant executions; they’re acts of worship and declarations of identity. When Rose encounters Christabella and her followers after 30 years of isolation in a nightmare world, they have no interest in escaping it. This nightmare is exactly the world that the cult wants: one that consists only of their traditions, in which all their paranoid doomsaying is validated. The daily horrors of the town are welcome (in one scene, Christabella is utterly unmoved when the youngest member of her cult is flayed alive by a monster while out scavenging for food, and seems almost pleased to declare that the death was predictable and justified). Instead it’s Rose, a young outsider, who is immediately seen as a threat to their world.

Both cults are socially regressive forces. What they want is to stop things from changing, and to achieve that, they gleefully toss children into the black pit of the old ways. Sacrificing the young isn’t an unfortunate cost to them - it’s half the point in and of itself.

In the context of the greater Silent Hill lore, all these themes were new.

Since the release of SILENT HILL the movie, it’s seemed kinda obvious to equate Centralia with Silent Hill. When I first heard about Centralia through Christophe Gans’ posts on the official blog, I remember going “oh, of course, that makes sense”, and I didn’t think about it any deeper than that. The film sparked a new wave of macabre tourism for Centralia - publicized in countless articles proclaiming it the “real-life Silent Hill” - which further reinforced the connection, while also making it seem not worth examining (“Yeah yeah, I know about the town that inspired the movie”).

But in reality, the only thing that the Silent Hill of the early games had in common with Centralia was that they were both ghost towns set in the United States - and even that’s a pretty tenuous similarity, since Centralia was only a “ghost town” for the short period of time between the relocation of its residents and the demolition of their homes; by the time SILENT HILL was being written, there were already only a dozen or so buildings left.

I think there’s something else going on here.

Unlike the Silent Hill of the games - with its entirely unique occult history - Centralia is the product of widespread and well-recognized patterns. Its fate isn’t a freak accident; it’s an inevitability. There was a mine fire because there were abandoned mines - because it was a boomtown, just like any other in the Rust Belt. The town was setting fires in derelict strip mine pits because they were trying to dispose of waste for cheap, because their municipal coffers had dried up when the coal industry abandoned them. The fire burned for decades until the town had to be evacuated, because the same infrastructural indifference that leaves these towns bleeding out slowly also means that there wasn’t any political will or funding to undertake the major projects required to save it.

Centralia didn’t become a ghost town because of some strange and unique event. It became a ghost town because it had already been left to die. Just like Possum Springs. Just like Brantford.

The reason why it feels so obvious to early-2000s American audiences that Silent Hill would draw inspiration from Centralia is because Centralia reminds us of the living ghost towns that so many of us are still stuck in.

An abandoned portion of Pennsylvania Route 61 outside of Centralia in 2013. Nicknamed “Graffiti Highway”, it was buried in April 2020 by mining company Pagnotti Enterprises. Photo by Dan Gleiter

And, as hokey as they come across in the finished product, the cultists from the film carry a bit more resonance than Silent Hill’s initial supernatural villains did. Whether these cults caused the town’s downfall (as in SILENT HILL) or were caused by it (as in NIGHT IN THE WOODS), they represent the same thing: the members of a community that are willing to sacrifice everyone else’s futures in their futile efforts to maintain a long-dead status quo. In their own way, they’ve internalized the same logic that led their industrialist founders to sacrifice workers (through preventable disasters and lethal conditions) when their pursuit of perpetual profits runs up against the limits of natural resources: When you can’t squeeze blood from hard coal, you get it from people instead.

The cultists in SILENT HILL proudly take lives to maintain their traditions. The outcome of this is shown through implication: there have been no children in Silent Hill since Alessa’s burning. The town has no future. The cultists in both SILENT HILL and NIGHT IN THE WOODS are doing to their respective (young) protagonists what it feels like living in these towns does to their (young) audiences.

It should be said that, although SILENT HILL and NIGHT IN THE WOODS are growing out of some of the same soil, they end up bearing very different fruit. For all the bitterness and despair in NIGHT IN THE WOODS, there’s also a lot of fondness. After all, the death of a town only hurts if you feel a strong connection to it; both Mae and the game’s creators still love their homes. And while the death cult is all that’s left of Silent Hill, the regressives in Possum Springs are very much not the whole town. Ultimately, impressively, the game is optimistic. It doesn’t lay out how to save the town, but it does suggest that the way the people in it can save each other is through community. As the game’s tag line says: “At the end of everything, hold onto anything.”

As for SILENT HILL…once again, the prose in the 2004 draft of the script makes explicit what the shots at the end of the finished movie were saying about the town’s fate, when Rose finally leaves:

Silent Hill was already dead. It was just waiting for the last remaining residents to fade away, leaving the site of so much intimate tragedy as just another anonymous patch of dirt, forgotten like so many others.

Of course, as interesting as all this is - as much as the film adaptation did introduce new and resonant themes to the Silent Hill series - it’s still true that I didn’t pick up on these themes for the first 15 years of watching this movie, even though I went into it badly wanting to like it.

So to close out, I wanted to talk about how I overlooked them for so long…and then how I found them, and what that taught me.

A brief autopsy of themes

This is a good time to revisit the ending of SILENT HILL a bit. Remember that hitting-you-over-the-head-with-its-messages climax I mentioned before?

Yeah…that one.

Earlier, I said it was kinda weird how Rose’s speech is presented like it’s supposed to be news to anyone. In the finished movie, she challenges Christabella, the cult’s leader, to “tell them the truth” - which, Rose explains, is that “you’re already damned”, because you “darkened the heart of an innocent”. It comes across like “Tell them the truth - that burning children alive is bad!”

Well, in the 2004 draft of the script, Rose doesn’t say that the cultists are already damned - she says they’re already dead.

And I don’t think this was meant to be a big twist à la THE SIXTH SENSE - it was just meant to be the dramatic thesis statement at the end. This draft had more clearly established the whole “dead town” thing in a couple other scenes that never made it into the final film.

The “truth”, in this draft, isn’t just that the cult kills people - it’s that all the death is for nothing. Despite Christabella leading what the remains of the town exactly as she wants, it’s still dead. The world outside is “alive and green and full of life” - it has left Silent Hill behind. The cult’s offerings of cruelty isn’t “keeping the darkness at bay”, as Christabella claimed - it’s keeping everyone in the darkness.

The reason that the dark force in Silent Hill needs Rose’s help to deliver that world-shattering truth to the cultists is because she isn’t from Silent Hill - she is the outside perspective that is poisonous to an isolated worldview.

At least, that makes sense to me.

Don’t get me wrong, Rose’s monologue in the 2004 script is still plenty hokey. Avary had said in an interview that “what [Gans] wanted from me was bombastic speeches,” which led him to try to turn “the dialog moments into […] this big, powerful, impressive moment where people are talking in hyperbolic terms and everything they say is quantifiably profound”, and uh, boy that sure explains a lot. But I do think that this more metaphorical angle for the final monologue might’ve played just a bit better than…well…

…whatever this is.

Now, as it turns out, we do have some insight into why the ending of the film might’ve changed from the 2004 draft of the script to what we got in theaters.

Originally, after Rose’s speech, a parade of monsters (specifically, the iconic “Red Pyramid Thing”, a.k.a. “Pyramid Head”, from the second Silent Hill game) break into Christabella’s church and massacre the cultists, with one of them carrying Alessa’s burnt body in “a monstrous parody of a nativity scene” to observe the carnage.

But, as Gans explains in the director’s commentary for a French special edition BluRay release, they had already used up the days that were needed to shoot the finale as written, and the producers refused to pay for any extra days of filming. To fit into the remaining schedule, the scene was changed to only feature one monster: Alessa herself, now controlling a swarm of CGI barbed-wire tentacles snaking out from her hospital bed.

Concept art for the finale of SILENT HILL that was intended to be shot, featuring several Pyramid Heads enacting Alessa’s revenge

Instead of the dozen or so Pyramid Heads, the version of this scene that got made only involves Alessa herself

With Alessa being promoted from an onlooker in the film’s climactic bloodbath to its supernatural executor, parts of Rose’s monologue immediately preceding it probably needed to be tweaked a bit to fit (the finished film has Rose end with “and now you cower in the face of Alessa's revenge”, for example). These adjustments would be minor, but it’s not hard for me to see how a flurry of last-minute tweaks ends up with a monologue that feels very different from how it started - especially without any time to work out all the kinks. (This might partially explain why the choreography for Rose’s monologue is some of the worst in the film, too.)

Looking into the development of SILENT HILL, you see lots of similar indications that some pretty significant parts of the film were sliding around throughout its production. Here’s just a few examples that jump out to me:

Initially, Rose’s daughter suffered from life-threatening seizures. In the final film, this was replaced by sleepwalking, and all the dialog referencing the daughter’s seizures was changed…leading to a final film where Rose tells every stranger she meets that her daughter sleepwalks, which isn’t really relevant when looking for a missing child (unlike seizures).

The final film still includes a small-town cop telling Rose “You people - you get off the highway, from whatever big city, bringing all your sick problems with you”, but the storyline where Rose had been from Chicago driving into the rural Bible Belt was dropped. Instead, Rose’s house was now in the woods - looking decidedly less urban than Silent Hill itself. (Other behind-the-scenes interviews suggest that the exact location for Rose’s home was determined much later than expected.)

On the official blog, Gans mentions that he came up with the idea for a brand new monster that wasn’t in the script, two days before the scene involving it was going to be shot. This monster was played by the film’s choreographer, who would’ve played each of the Pyramid Heads in the original finale, so maybe this is where some of those shooting days went.

Oh, and this one’s really conjectural, but I’ve had a chip on my shoulder over this since the film came out, so I’m gonna say it anyway: In the final film, there’s an absolutely cringe-inducing plot dump near the end, where the dark force just directly narrates the entire backstory of Silent Hill and Alessa, done via voice over on top of a flashback sequence. I don’t have anything concrete to suggest that this was the result of someone panicking that the film’s story was too hard to follow and shoving it in during post-production, BLADE RUNNER style, but man, it sure looks like it. The narrator literally says “Congratulations for solving all the puzzles, protagonist, your reward is plot”, like it’s a fucking video ga- ah. Hrm.

Here’s the thing, though.

Despite all the way-too-direct dialog, the occasionally confusing editing, the sometimes attention-grabbingly bad choreography….you can still find the cool stuff in SILENT HILL.

All these themes I’ve been talking about that it feels like you see more clearly in the 2004 script - about Silent Hill’s residents refusing to acknowledge the “post” in “post-industrial town”, about sacrificing the future to an already-dead past - they’re actually all still there in the finished movie, too.

How I learned to stop worrying

and love the bomb

When the 2004 script surfaced on the forums of fan site Silent Hill Heaven, many posters who had been disappointed by the finished movie were quick to praise it.

This is pretty typical. When you’re unhappy with what you got, then the version that could’ve been is usually going to look better - even though the 2004 script isn’t really that different from the final shooting script in terms of overall quality.

Sure, there’s some really bad dialog in the movie that wasn’t in the 2004 script. But there’s also some really good stuff that wasn’t in the 2004 script (“Many different forms of justice, Chris. See, you've got man's, God's...and even the Devil's”). And some other really bad lines from the 2004 script that rightly didn’t make it into the movie (“It’s not Judgment Day, but it is a day for judgment!”).

It’s not just dialog, either. The final movie added that terrible third-act plot dump, but the ending once Rose leaves the town is much better than in the 2004 script, which had ended with a generic “and they lived happily ever after…oR DiD tHeY?!?!” stinger where Rose’s daughter looks in the mirror after escaping Silent Hill and we see that the reflection is sinister.

Besides, scripts change - that’s just how it goes when making something as big and complex as a 50 million dollar film. As Avary had said back when he finished that draft of the script in October of 2004: “Keep in mind, no script is a movie. It's a blueprint toward production...and the blueprints tend to change along the way.” It’s pretty common for movies based on major licensed properties like this to be put on a more expedited schedule - which is going to lead to more things being compromised and improvised, no matter what your script says.

But when you’re a disappointed fan, you want a scapegoat.

For years, mine was Roger Avary. Reading the official blog, I thought that Christophe Gans “got it”, and therefore it must’ve been Avary who fucked it all up.

For a lot of other fans, their scapegoat was Sean Bean - who played Rose’s husband, Christopher.

Christopher didn’t have any analog in the games, which meant fans were primed to hate him from the start because he represented a brand new character. Remember, there are Silent Hill fans out there who think that anything short of getting the street names and locations exactly right is a sign of profound apathy in adaptation.

But there’s more going into the hate that this character got from fans on the film’s release.

Right around the film’s release, both Avary and Gans were giving interviews saying that they didn’t envision Christopher being a significant part of the film - but producers sent the 2004 draft of the script back with a note reading “There’s no men in this!”, so Avary fleshed out the role some more. As this anecdote made the rounds, it fed a narrative among fans that Christopher was more the brainchild of misogynistic producers than part of the intended vision for the film.

(For the record, Avary said in interviews that it was a good note. I don’t agree, but I also don’t think it was this note that stopped the movie from being some feminist horror masterpiece. Gans seems to have some pretty messed up ideas of motherhood and femininity on display in this film that could be the subject of a whole other essay…so I don’t want to suggest that Gans’ initial “estrogen-filled” vision for the film - as Avary put it - would’ve been especially progressive if the producers didn’t interfere.)

Adding to this, the behind-the-scenes featurette that was included with DVD and BluRay releases noted that Sean Bean was the last to be cast for the film - and the clips from his interviews indicated he wasn’t as familiar with or invested in the source material as Gans was. To fans of the games, the message was clear: Sean Bean didn’t belong here. Sean Bean is not a True Gamer.

So, Sean Bean became the poster boy of the studio meddling that fans blamed for ruining their film.

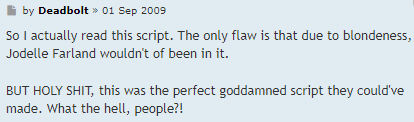

Just like with STAR WARS EPISODE 1: THE PHANTOM MENACE, there were a bunch of fan edits of SILENT HILL almost immediately. Like most fan edits, these are generally subtractive - i.e. they mostly consist of cutting out things that they thought “shouldn’t have been” in the movie. While THE PHANTOM MENACE’s much more numerous fan edits show a wider variety of approaches to that movie’s least-popular character (some tried to edit Jar Jar Binks out as much as possible, some re-dubbed him with a different accent, and some even re-dubbed him in a brand new alien language), all the SILENT HILL fan edits agreed on what to do with Sean Bean’s character: cut him entirely.

Info about the “Red God Remix” fan edit of SILENT HILL

Now, I don’t want to be too hard on fan edits here.

For one thing, pointing out the technical and structural shortcomings of these things is kinda like pointing out that someone’s YouTube video of DRAGON BALL Z and BLEACH scenes set to a Linkin Park song aren’t as good as the band’s official music videos. These are amateur products that are usually made without any professional resources. That’s not exactly an insightful analysis by itself.

But also, I was working on my own fan edit of SILENT HILL around then, too.

I kept notebooks where I scribbled time codes down, trying to figure out how to make Rose’s final monologue less godawful. I worked on it for months. (Again, instead of a lot of my actual classwork - my love for film was manifesting as one of the things stopping me from transferring into film school.) I never finished it - couldn’t save up the money to buy the stuff I needed - but even though I wasn’t focused on the same things as other fans, I’m sure it wouldn’t have been any better than what’s out there. Just like the folks behind the anti-Sean-Bean edits, I felt like I was trying to salvage my appreciation for this movie that I had so badly wanted to love.

But this was, ultimately, misguided.

The fan rage aimed at Sean Bean is referred pain; Sean Bean isn’t actually the source of the movie’s underlying problems. As one friend puts it: “It’s Sean Bean; he’s not going to damage your film.” Even some of people behind fan edits that removed his character said they didn’t mind his performance.

Films on the level of SILENT HILL are, no matter what the final product looks like, incredibly complicated to make. The different crafts that go into filmmaking are deeply interwoven, which makes it notoriously difficult to try to zero in on just one aspect (e.g. the script) from looking at the final product. So when you’re making a fan edit, you can’t actually separate out one aspect of the production process - you can only cut chunks out of the finished quilt. The result might not have the bits you hate, but it isn’t any better at keeping you warm.

There’s necessarily some amount of babies that get thrown out with the bathwater when you go about trying to “salvage” a piece of media this way. When you’re cutting a character out of a movie because he “shouldn’t have been there”, you’re not engaging with the finished product for what it is. And you’re going to miss some potentially really interesting stuff.

I’ve watched some of these fan edits, and none of them sparked a feeling of “Finally, this is what I had wanted all along!” Cutting bad dialog or side characters didn’t save SILENT HILL.

NIGHT IN THE WOODS did.

My friend making the comparison between the two did.

That’s what got me to look past my disappointment and wonder what the film was trying to say.

NIGHT IN THE WOODS gave me a lens to use on SILENT HILL that let me see really cool things that I had never found despite more than a decade of watching that film and researching Centralia and engaging with Silent Hill fan communities. Things that had been there all along.

So, is SILENT HILL a hidden gem?

No, that doesn’t feel right. It’s too mainstream to be a hidden anything. And lots of reasons why some of the neat shit in the movie seems “hidden” is because it’s buried under some legitimately mediocre storytelling decisions and sloppy executions. Its problems can’t be climbed over just by “giving it a chance”.

But that’s not the point.

The punchline here is…it doesn’t really matter if any of this stuff changes whether SILENT HILL is Good Actually™ or not.

Finding cool shit in a piece of media can be more rewarding than just deciding if it’s good or bad.

That’s been the real fallout of my friend’s insightful comparison of something I loved with something I was disappointed by. And I really needed that, especially these days.

I don’t know if this is the result of living during Peak Media, with an endless backlog of stuff to watch/play/read, with alternating waves of hype and fear-of-missing-out, with so much discourse subsumed by the Take Economy. I’d been feeling so much more pressure to “choose right” when I finally did sit down with a piece of media, which is a real force multiplier for disappointment/frustration when it turns out to not be very good. And especially after 19 months of being ragged by a pandemic that’s really putting the “terminally” in “terminally online”, every public assessment of a new movie/game/show feels like a line drawn in the sand with troops at the ready.

It’s exhausting.

But the truth is, whether we think something is “good” or “bad” often has a lot to do with the context in which we consume it - whether it arrived when it was just what we needed, or when we were tired of things like it. (Maybe I’d have been less inclined to pick Roger Avary as my angry-fan-scapegoat if I’d known he also co-wrote PULP FICTION. Or maybe that would’ve made me hate him more.) And the “final grade” of a thing generally matters less than an actual descriptive analysis of that thing, one that really engages with it and digs up all the fascinating bones buried in it. That’s part of why the reviews that I write here use emoji instead of number scores or recommendations. That’s part of why I love analyzing things I think are bad. That’s part of why I came back to Silent Hill.

This is one of the core lessons of NIGHT IN THE WOODS.

The relationship that Mae and her friends have to their home is complicated. Possum Springs is stifling. They need to escape it to survive, they write songs about wishing they can at least manage to die anywhere else but in Possum Springs, and they mock the town’s pride in its long-since-faded history. But they also cherish their own history within the town, or at least, parts of it - their childhood memories, what their kooky art teachers pulled off with underfunded programs, the local traditions that they wore like colorful costumes on holidays. Possum Springs is both their jailer and their cellmate.

At the end of the game, the town is still fucked, whether or not Mae and gang dealt with the death cult of conservative uncles who were actively murdering their friends and neighbors. Like SILENT HILL, NIGHT IN THE WOODS isn’t about saving the town.

But pieces of it - memories, little things to love, the people in it - can be saved. Not forever, but at least for one day more.

NIGHT IN THE WOODS is about reclamation. Mae’s journey of understanding herself and her home isn’t about discovery so much as re-discovery: Seeing your lifelong friends through a new light. Revisiting a horror story your grandpa used to read you before he died. Digging up things that were already on brochures for tourists or in the library or rotting in flooded trolley tunnels.

The town itself is less important than what you find in it.

If you want more cool insights about movies from my buddy who sent me down this particular road, you can check out the podcast where he’s one of the hosts: How Have You Not Seen That?

Each episode features three friends discussing a movie that “everyone” should know but one of them hadn’t seen before, and explores both the film buff perspective and first-time reactions.