Re-making a monster

Izumi Kato graduated art school in 1992.

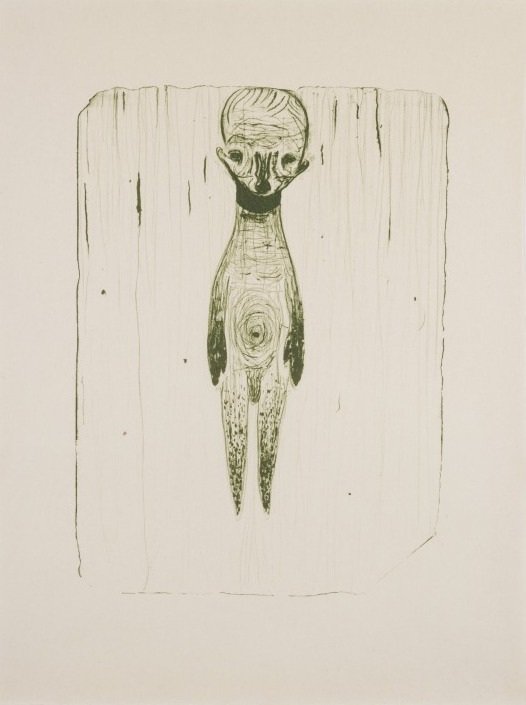

Untitled 2017 by Izumi Kato. Lithograph. Photo by Kei Okano

Disillusioned by both his classes and the desk jobs he worked after graduation, he next went into construction work for nearly a decade. When he returned to art after that, it was with a newfound appreciation for what he could make with his own two hands.

All of his sculptures are chiseled, stitched, and arranged by hand; and when he paints, he uses his hands instead of a brush. That applies to painting his sculptures, too - which gives his process a strange and intimate vibe, when you consider that all his subjects are human figures. One can imagine Kato caressing the pigment into the faces of his works.

Untitled 2009 by Izumi Kato. Oil, acrylic, wood, stone, iron. Photo by Keizo Kioku

Today, Kato is a successful contemporary artist, having been featured in solo exhibitions from Berlin to Beijing, from Paris to Puerto Escondido. But in the early 2000s, his art career was just getting started.

In April of 2005, Kato held his first “full-scale one-man show” at an art gallery in Tokyo. One of the installations featured a sculpture he’d made the year before: a giant fetal figure with a painted face, standing uneasily and leaning against the wall for support.

Untitled 2004 by Izumi Kato. Acrylic, charcoal, wood. Photo by Keisuke Yamamoto

Around this time, Kato’s works were often part of exhibitions with names like “Lonely Planet” and “Clairvoyants in this threatening age” - but Kato repeatedly insists that he doesn’t intend his art to have any particular messages. Instead, he hopes that his viewers will find their own meanings in his works. He refuses to even title them, hoping to avoid influencing his audience’s interpretations too much.

Then along came 4chan.

Actually, wait - first came DOCTOR WHO. (Probably, at least.)

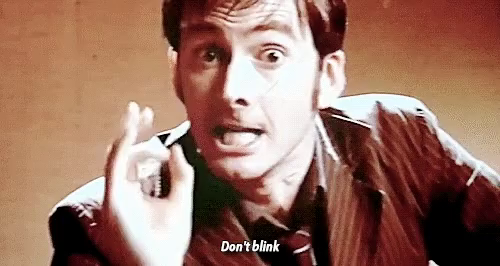

On June 9th, 2007, the DOCTOR WHO episode “Blink” aired for the first time. The plot mostly revolves around one of those “I am my own father” time travel paradoxes that have been all the rage since Robert Heinlein’s 1958 short story ALL YOU ZOMBIES (look it up), but the bigger reason why “Blink” got as famous as it did was the monster it introduced: the Weeping Angels.

Sally Sparrow (played by Carey Mulligan) in “Blink”, unknowingly being observed by a Weeping Angel

The Weeping Angels are otherworldly predators that are only able to move when no-one is looking. While someone watches them, they appear to be ordinary statues. When that person stops watching - even for just a blink - they move with terrible speed and ferocity.

It’s a neat idea, especially for a BBC show that wants all the cheap monsters it can get.

The Weeping Angels were an instant hit, quickly becoming an iconic Doctor Who monster (in one episode, the Statue of Liberty gets turned into a Weeping Angel), and the Doctor’s wild-eyed warning of “Don’t blink!” is one of the most memorable moments in the show.

The Doctor (played by David Tennant) giving his life-saving advice in “Blink”

OK, now here comes 4chan.

4chan’s /x/ board was started in 2005 as a general photo board, but was soon after designated its “paranormal” board. It was home to both sincere conspiracy theorists and amateur sci-fi/horror writers.

On June 22nd, 2007, a 4chan user with the handle The U.S.S. Walrus posted a short piece of sci-fi horror prose on /x/ about a malevolent statue that can only move when you aren’t looking at it, designated “SCP-173”. When someone is in its vicinity but not directly observing it, it will either strangle them or snap their neck, moving with impossible speed “in the literal blink of an eye”.

The post describes the “containment procedures” for this supernatural object, written from the dry and clinical perspective of a technical manual or workplace safety policy, which set the story apart from the other “I swear this happened to me” stories in /x/.

An aside

For years, the FAQ on the official SCP wiki claimed that the original 4chan post for SCP-173 was created “a couple of months before the Weeping Angels”.

In October of 2018, digital archivist Jason Scott surfaced a trove of 10 million old 4chan posts from 2006 through 2008, and it appeared that the earliest record of the original SCP-173 post was made after the initial broadcast of “Blink”, but before it was broadcast in the US.

In December of 2018, the “Is SCP-173 based on the Weeping Angels?” entry in the FAQ was updated to no longer assert that it was definitely “a coincidence”, though it does still suggest that SCP-173 might’ve been conceived independently anyway.

The U.S.S. Walrus also included a picture to accompany their post: Keisuke Yamamoto’s photo of Untitled 2004 by Izumi Kato. Walrus’s original description of SCP-173 is also based on that specific photo. It incorrectly described the sculpture as being made of concrete, rebar, and Krylon spray paint, but it referred directly to the room seen in the photo, and decided to spookify the rusty floor by suggesting it was covered in “a mixture of feces and blood”.

This little post on 4chan was also an instant hit within its niche, and inspired fans to create their own stories in the form of “containment procedures”.

Early reactions on 4chan (archived)

In 2008, a wiki was set up to be able to organize the stories people were writing somewhere outside of 4chan. Eventually the fictional organization behind these procedures was dubbed The SCP Foundation, and the creepy things it contained were called “SCPs” (borrowing the terms from Walrus’s initial post, although Walrus themselves wasn’t involved in the creation or running of the wiki). An edited version of the SCP-173 post, complete with the accompanying photo of Untitled 2004, was among the first entries added to the new site.

In July of 2008, The U.S.S. Walrus joined the SCP wiki and identified themselves (now under the handle “Moto42”), and expressed awe at what their little chunk of prose inspired. But things were just getting started.

The SCP wiki now has over ten thousand entries. Its contents have been adapted into graphic novels, stage plays, songs, and dozens of video games - including one big-budget release in the form of CONTROL (which doesn’t directly reference the SCP Foundation, but has its own analogous organization that contains similar sorts of spooky objects, like a fridge that becomes dangerous when it isn’t being directly observed by someone).

SCP - CONTAINMENT BREACH (2012)

CONTROL (2019)

The games were a big deal, particularly the indie titles like THE STAIRWELL and SCP - CONTAINMENT BREACH. These came out in 2012, right in the middle of the great creepypasta wave, and were swiftly showcased by celebrities like Markiplier - which led to a huge surge in the popularity of the SCP project. Of the indie games, SCP - CONTAINMENT BREACH remains the most popular, and the main monster to avoid in that game is SCP-173.

Like many things on the internet, the SCP project grew much faster than it matured. At some point, the wiki had to start answering some grown-up questions about licensing and intellectual property.

Questions like: “Doesn’t Izumi Kato hold the copyright for his art, which is displayed as part of SCP-173?”

I’ll bet you can guess the answer to that one.

This is actually a picture of photographer Nobuyoshi Araki, not Izumi Kato. But you get the idea.

In 2014, Kato got in touch with the staff of the SCP wiki. While he was upset at how his intentions for Untitled 2004 were usurped by the SCP project, he was also understanding of the fact that the sculpture (now affectionately referred to as “Peanut” by fans) had become a widely-recognized icon for SCP.

So, in a surprising moment of everyone being really chill about everything, Kato allowed the wiki to continue to display Untitled 2004 on SCP-173’s page, provided that they added an attribution to Kato and that no-one used the image of Untitled 2004 for commercial gain. The staff were happy to oblige, and brushed aside the few complaints that the attribution ruined the “immersion” of the piece. Everything went better than expected.

Still, the SCP wiki staff legitimately (and correctly) felt bad about the situation. Untitled 2004 had been taken over by SCP-173, and they wanted to do right by a fellow artist - one to whom they owed an enormous debt of gratitude.

So, in February of 2022 (large community projects like SCP don’t make decisions quickly), the staff announced that they were removing the image of Untitled 2004 from the page for SCP-173.

But if that were all that happened, I wouldn’t be writing this.

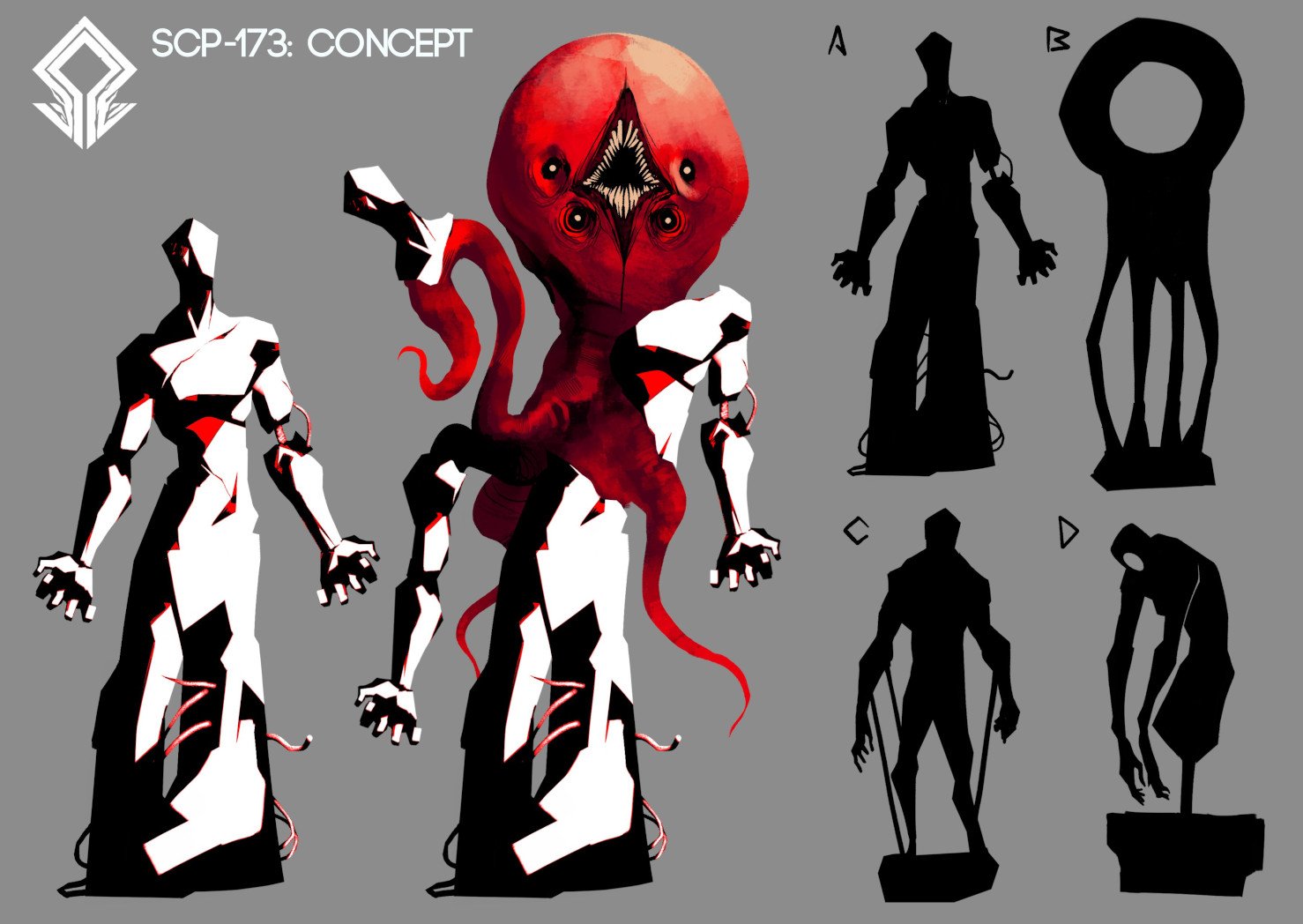

When the decision to remove Untitled 2004 was made, Moto42 contacted the wiki staff. As the original author, they requested that no replacement image be uploaded to the entry for SCP-173. Perhaps deliberately channeling Izumi Kato’s ethos, Moto42 explained that their intention was “to allow everyone to envision SCP-173 for themselves”.

In keeping with Moto42’s wishes, the community event that followed wasn’t a contest to pick the new face of SCP-173, because there would be no winner. Instead, in the truest spirit of a collaborative media project, everyone was invited to contribute their own vision of the icon.

And, in doing so, they reversed its inspiration: While the entry for SCP-173 was initially made to describe the art that accompanied it, the new art being made for SCP-173 was being designed to match the description.

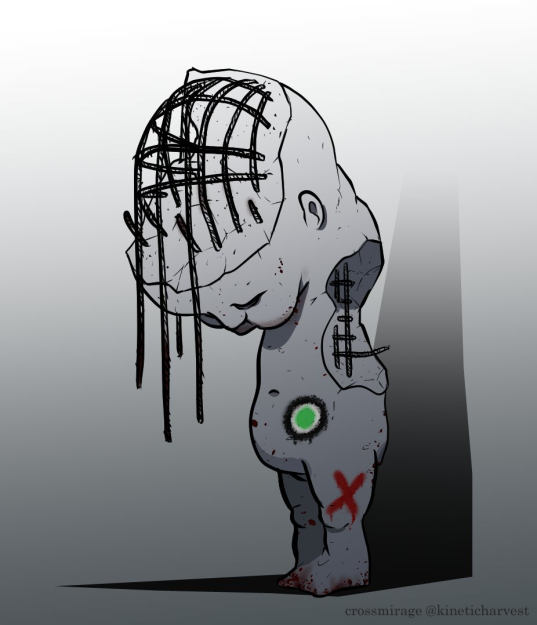

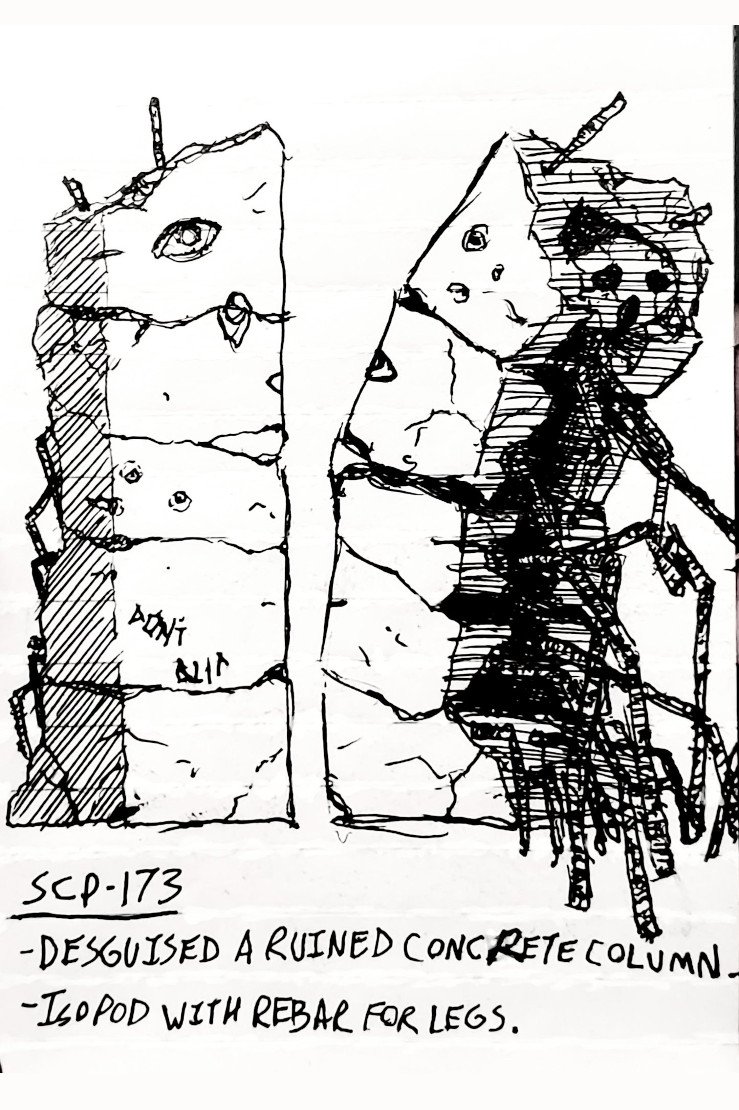

Moto42 initially described the sculpture as being made of concrete, rebar, and Krylon spray paint. At first, this description was mostly just a misidentification of the materials Kato used to make Untitled 2004. In the redesigns, however, each of these components became an foundational element for SCP-173’s new look.

For example: Rebar is usually internal, so why would it be visible? Is it an abstract sculpture? Is it a conventional statue that’s falling apart?

By @na_naturbii

And that spray paint - was it always there, somehow an innate part of the object? Or was it put there by people who encountered it? The latter might explain how the person writing the description knows the specific brand of spray paint that appears on the concrete: because they saw a previous victim applying it.

Plenty of artists submitted versions where someone had scrawled “don’t blink” on the statue (reinforcing the connection to Doctor Who and the Weeping Angels, intentionally or otherwise), but just as many instead opted for other imagery - like stylized eyes all over the concrete.

What about the thing that makes SCP-173 anomalous in the first place - its ability to move when unobserved? For some artists, the redesign was an opportunity to show how it achieves that behavior.

In DOCTOR WHO, the answer is straightforward: the Weeping Angels simply move as normal when no-one is looking, they just freeze in place like Andy’s toys in TOY STORY when someone turns their way. But that’s not the only way to represent the gimmick of “only moves when it isn’t watched”.

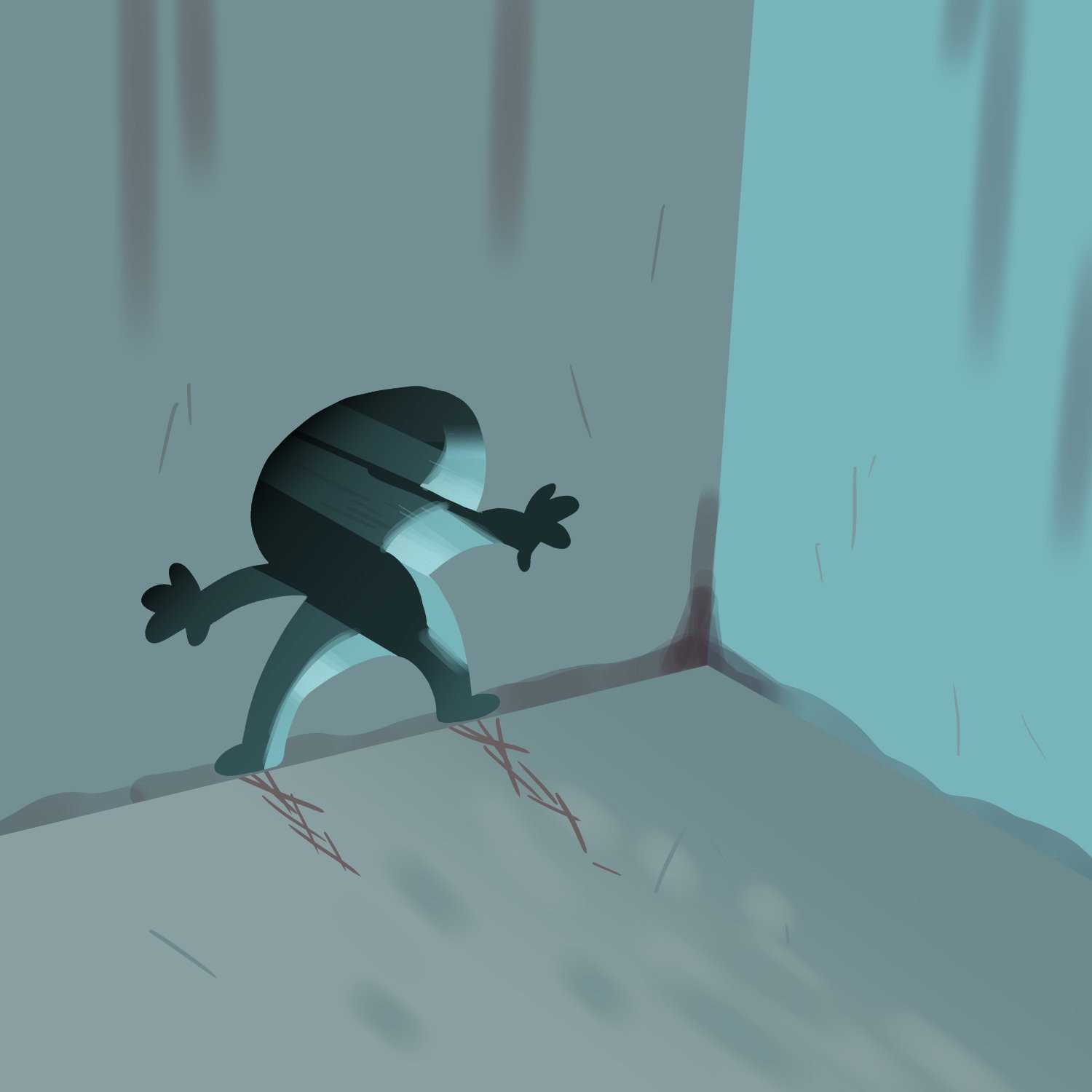

In some SCP-173 redesigns, it isn’t the statue that moves - it’s something inside it.

By @crim_reaper

Other artists preferred to double-down on SCP-173’s movement being unexplainable, and made designs to emphasize its immobility.

Trey Bishop, a concept artist who shares Izumi Kato’s passion for building things with his own hands, exaggerated specific parts of Untitled 2004 to get that effect: the fetal features of the sculpture are even more pronounced and the small limbs have been removed entirely, resulting in an object that, like a newborn, can’t even stand upright on its own.

By Trey Bishop

On top of that, the direction of the spray paint drips indicates that it’s laying upside-down. Everything about this design denies locomotion, which serves to further highlight the central question of SCP-173: How, physically, does it do what it does?

And not just “How does it move?”, but also “How does something that can’t move, strangle its victims?”

Personally, I prefer the mystery and surrealism of these sorts of designs over the generic “scary faces” that the Weeping Angels made when they chase people - but I’m not here to dictate the “right” way to enjoy these monsters. If anything, all these designs highlight just how many different ways you can make a simple concept like SCP-173 memorable and strange.

For one last example, consider the design submitted by Andrew Tsyaston, a.k.a. Shen of Shen Comix.

At first I thought this adorable guy was just a gag submission. Then I read the little story and follow-up image that accompanied it, and smiled in appreciation.

“SCP-173 is watched at all times by three foundation personnel via security cameras. They are required to warn each other when they are about to blink. However, in one incident, due to a lapse in communication, there was a three-person blink overlap of 0.092 seconds.

In this time, SCP-173 managed to move 8 feet into the 12 foot solid steel barrier separating it from the observation room, leaving a hole in the shape of its body behind it.”

What’s more SCP than something you think you understand, surprising you with behavior that’s as threatening as it is opaque? In a world where horror is a popular form of entertainment, it often feels like the strange is more unexpected than the scary.

All of the official submissions for the redesign of SCP-173 are collected on the SCP wiki; check ‘em out if you want more - these are only a sampling of the wonderful art there.

Beyond the art, though, one thing strikes me about this conclusion to SCP-173’s story: it’s a sign of how far the SCP project has come. And I don’t just mean how famous it’s gotten.

See, in the beginning, the SCP project was fixated on canon.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing. Discussions about a shared canon led to the creation of the fictional organization’s name (i.e. “the SCP Foundation”), the selection of a logo for that organization, and the establishment of shared terms (like “D-class personnel”, “cognitohazard”, and the various safety designations) that provided some common fixtures to unify and connect the works within the overall project.

The first “SCP logo”, based on SCP-529 (“Josie the half cat”)

The current logo, based on the 2009 design by user far2

But fiction projects about the unexplained have a tendency to draw in people who want to explain them. Everyone has their own big idea for what’s really going on; everyone wants to be the one to resolve the big questions: Who are the high-ranking staff of the Foundation, and what powers come with that status? Where do all the disposable D-class personnel come from? What is the over-arching “big bad” of this setting?

There’s a desire to not just contribute, but to override the contributions of others, to be the first person to plant your flag in unclaimed canon.

From the beginning, the SCP project wasn’t just a collection of ideas for stories - it was also the stories themselves. Some of the most popular early contributors to the project wrote interconnected narratives involving specific characters and events. And because there were fewer restrictions on who could edit what in the beginning, some of these stories often did things to other people’s work.

Even the site administrators would get in on it. In 2008 and 2009, when an SCP entry was deemed not good enough to stay on the wiki, it would be “decommissioned” - a process in which one of the admins would write prose where their author-insert character would destroy the SCP in question, before taking the entry down. Disliked authors weren’t just chastised in the real world, they were chastised in the fiction, too.

Anyone familiar with the online roleplaying scenes of the early 2000s can guess how this went.

When your community blends its canon with its administration, differences in taste metastasize into personal feuds. On the tamer side, disagreements over what sort of fiction should be on the wiki turned into stories where the admins’ self-insert characters fought each other. Other times, there was site vandalism, threats of legal action, and all the other forum drama you’d expect.

Online communities don’t always survive these growing pains. To make it, they have to grow past the egos and philosophies of their first movers and first celebrities. Maturity requires relinquishing control.

The modern SCP project is a very different place.

Today, many SCP fans will tell you that the number one rule of SCP is: “There is no canon.”

The official Guide for Newcomers makes this explicit: “Every article on the site is allowed to contradict and disregard any other article, no matter how well-known or popular.”

For SCP, there was no sacred cow more well-known or popular than Peanut.

Untitled 2004 was part of the very first SCP entry written, and after years of being the perpetual exception to every new rule and policy that SCP’s Licensing Team implemented, it was the final piece of copyrighted media to be removed from the wiki. As one mod put it:

“Remove [Untitled] 2004 and let 2008 finally end.”

The excision of Untitled 2004 from SCP was a culmination, a redoubled commitment to both authorial control and to shared authorship.

The art event wasn’t just a celebration of SCP-173, but of what the SCP project had grown into.

Today, the SCP-173 fan redesign gallery links to a “revised entry” for SCP-173 - a story from 2010 in which SCP-173 replicates itself, resulting in the deaths of several of the old admins’ self-insert characters - both a graveyard and a snapshot of the site’s history. The link to this “revised entry” is meant to suggest that the fan-made images in the gallery are depictions of all the new SCP-173s out there, to provide an in-universe explanation for all the art contributed.

But that’s just one story. The entry for SCP-173 itself is also still up, with no major “revision” to its content other than the simple removal of a photograph. If you weren’t familiar with its anomalous history, you wouldn’t notice anything amiss.

There is no official explanation for what’s going on with SCP-173, only edit logs and fan works.

There is no canon, only community.