Dinosaurs are weird (and that rocks)

Near the beginning of JURASSIC PARK, there’s a scene where a paleontologist is excitedly exclaiming all the bird-like features he’s noticing in a newly discovered fossil specimen of a then-little-known dinosaur named Velociraptor mongoliensis.

He’s interrupted by some bratty kid who remarks that if dinosaurs are like birds, then they’re not so scary. The paleontologist responds by explaining how this dinosaur would disembowel the kid and eat him alive, and we all share a laugh. The message seems pretty clear: None of the science makes these animals any less badass.

(And also, paleontologists had known these animals were extremely birdlike for decades, which is why this scene is even in the movie to begin with.)

The funny thing is, JURASSIC PARK kinda ended up turning everyone into that kid.

For instance, when it made Velociraptor world-famous virtually overnight, it taught everyone that they looked like this:

That’s pretty scary and badass! But in reality, the animal looked more like this:

Art by Frederic Wierum

For almost everyone (at the time, at least), JURASSIC PARK was their first impression of this animal. And so, when this spotlight started to include what paleontologists knew about the actual creature, lots of people were understandably pretty unimpressed with the “new look” of Velociraptor.

Art by James Ormiston

Don’t get me wrong. I love the dinos in JURASSIC PARK. And I’m not saying every movie or show or game that wants to include any dinosaurs should treat itself like a documentary. I’m not even saying dinosaur depictions in fiction need to be accurate at all.

Hell, in DINO CRISIS 3, the “mutant velociraptors” look like this:

Really, go nuts. We’re all tired of random clickbait going “bet you didn’t know that the dinosaurs in JURASSIC PARK aren’t accurate! bet you didn’t ever hear that over the past 30 years! bEt YoU dIdN’t KnOw!!!”

But the thing is.

Since then, most crowds treat any new discoveries about dinosaurs kinda like Neil deGrasse Tyson tweets - i.e. like unwanted intrusions on a beloved memory, that begin with a scoff and a “Well, actually…”. As though real paleontologists were out to convince you that the awesome screaming monsters from JURASSIC PARK should’ve been just, like, some dumb prehistoric turkeys or something.

So now, whenever anyone brings up new dino research, someone in the group just has to say “I still think they look dumb with feathers”. It’s like the paleo equivalent of when people preen themselves over how little they know about American football whenever the Super Bowl comes up.

Of course I found your generic toothy T-rex knock-offs to be cool when I was a kid. (Hell, when I was a kid, I thought mammals were categorically uncool. When my parents brought home a pet dog, I’d wanted an eel.) But by these days, they’re familiar. They’re obvious. They’re boring.

So fuck it. I’m gonna put feathers on all the monsters you grew up loving. You can’t stop me.

What’s more: I’m going to get you completely pumped for that.

I’m gonna show you how dinosaurs are so much bigger and crazier than your childhood memories. Feathers are just the beginning.

Let’s start with those memories, then let’s punch a hole in the bottom and see how deep the rabbit hole really goes.

Bigger and stranger

The 1990s was a pretty fucking rad time to be a kid who was into dinosaurs, and that's not just because of the release of JURASSIC PARK in 1993 - there were also some pretty cool discoveries happening around then.

Before the 90s, a major part of Tyrannosaurus rex’s claim to fame was that it was the biggest carnivorous dinosaur ever. In pop culture, this made it the coolest dino. But in 1993, a new genus was discovered that might be even larger. This genus was named Giganotosaurus in 1995, and “bigger T-rex?!?!?!” was good for about as much fame as a paleontological discovery could get - quickly making its way into some children’s media, too. I remember reading DINOTOPIA: THE WORLD BENEATH, which featured a spread illustration focusing on introducing Giganotosaurus as bigger than T-rex (and this book came out the same year that the species got its official name).

Tyrannosaurus rex (left) is faced down by Giganotosaurus carolinii (right) in DINOTOPIA: THE WORLD BENEATH, introducing the newly-discovered dino to kids who already knew T-rex as the biggest. Illustration and story by the incredible James Gurney

But there had already been a challenger to the throne of “biggest meat eater” before then: Spinosaurus aegyptiacus. We’d known for decades that Spinosaurus was around the size of a T-rex, but a slew of new specimens in the late 1990s put Spinosaurus back on people’s radar - which, again, made some pop culture ripples because “bigger than T-rex?!?!?” Then, Spinosaurus very quickly got more famous than Giganotosaurus, the same way that Velociraptor got famous: It starred in a Jurassic Park movie. In 2001, JURASSIC PARK 3 featured Spinosaurus as its main villain (alongside Velociraptor), establishing that it was the new hotness by having it kill a T-rex early in the movie. From the mid-2000s to the mid-2010s, updated estimates would solidify the fact that Spinosaurus could indeed grow to be substantially longer than T-rex (~50 feet versus ~40 feet), and it is currently believed to have been the longest terrestrial carnivore to have ever lived on Earth.

Tyrannosaurus rex (left) faces off against Spinosaurus aegyptiacus (right) in JURASSIC PARK 3, in a scene that sparked tons of arguments that are basically the pop-paleontology version of whether Goku could beat Superman

But, more excitingly, the mid-to-late 2010s also brought around further refinements of what Spinosaurus looked like and may have lived like - including some real back-and-forth debates as new findings get challenged by even newer findings. And that’s what I wanna talk about here. Like any dinosaur that we’ve known about for a long time, our understanding of Spinosaurus has changed a lot over time. (The phenomenal YouTube series Your Dinosaurs Are Wrong is based entirely on this, complete with animations visualizing these changes.) And Spinosaurus is really weird and really, really cool.

First, lemme back up and introduce this bad boy a bit more.

Ernst Stromer’s 1936 reconstruction of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, based on the fossils found in 1912

The first Spinosaurus specimen we know of was discovered in 1912 by Richard Markgraf and Ernst Stromer, and officially named “Spinosaurus” by Stromer in 1915. Although he only had a few bones, Stromer immediately knew it was kinda weird: For one, it had these huge spines on its back, after which it is named. For two, its dentary bone (lower jaw) was pretty crocodile-like: it was long and narrow, with wide-set conical teeth. Despite this, though, when Stromer visually reconstructed the rest of the animal in 1936, he played it pretty safe - filling in the gaps with generic theropod features. As a result, Spinosaurus’ earliest depictions were basically just “Allosaurus, but with a sail on its back”.

Stromer played it less safe in other ways though, as his defiance of the Nazi party made an enemy of the collections manager of the museum where Stromer’s specimens were housed. The manager refused Stromer’s requests to move the fossils to safer locations (as other curators were doing) during World War II, and they were all destroyed by bombing in 1944. We wouldn’t get more Spinosaurus specimens for half a century - but in the 1990s, more fragmented remains started trickling in.

Would you believe me if I told you that instead of a signature roar, its calling card in JURASSIC PARK 3 was a Nokia ringtone from someone it ate at the beginning? Seriously

By the time JURASSIC PARK 3 rolled around, we’d corrected several elements of Stromer’s depiction. We didn’t show these animals walking upright dragging their tails on the ground anymore, and we portrayed Spinosaurus with a more crocodilian head. But overall, it still had a very “generic theropod” look - like you just put a croc's head and a Dimetrodon’s sail on a T-rex. (Oh, and beefed up its arms - everyone knows that one of the distinctive features of T-rex is supposed to be its itty bitty arms.) Even its namesake sail is little more than a hump at this point. Fortunately, these features were just distinctive enough to keep the toys coming.

Then in 2014, Nizar Ibrahim and colleagues presented a new specimen that was much more complete than anything we had before. Notably, it included the arms (which turned out to be much bigger than expected) and the legs (much shorter than expected). Oh, and the sail has this funky M-shape.

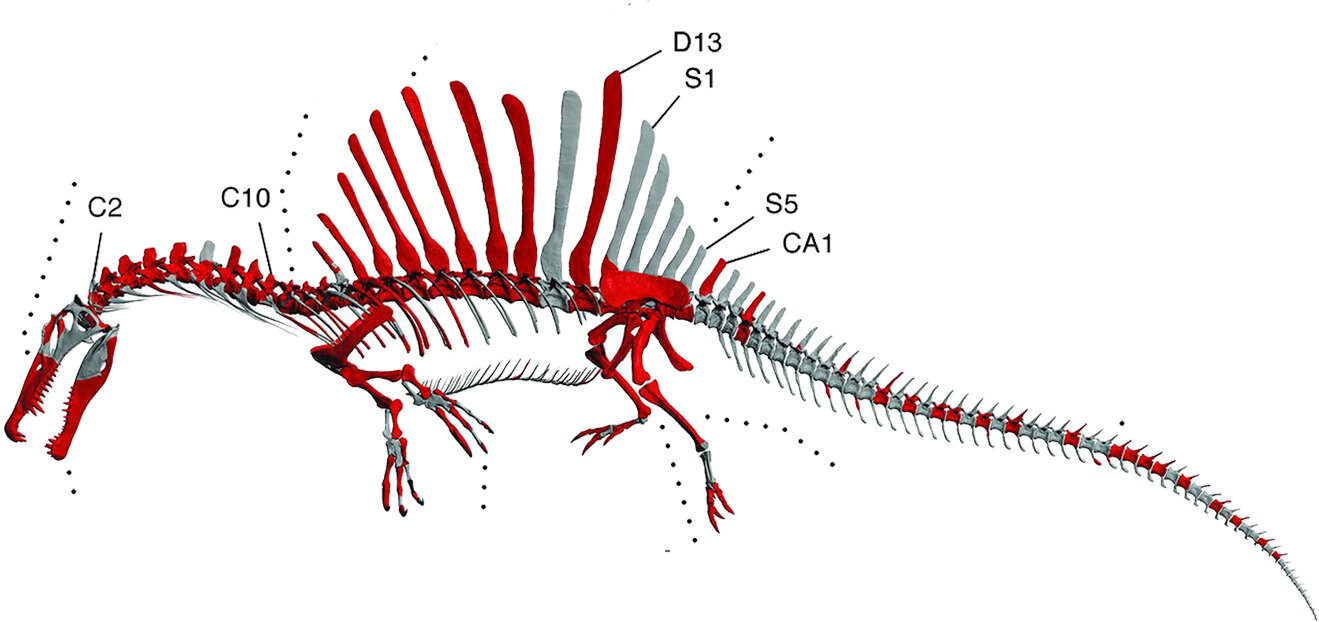

The updated reconstruction of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus from Ibrahim et al in 2014; the bones found in this new specimen are shown here in red

These additional findings junked the “T-rex with a hump” depiction, and led the depiction to more closely resemble a modern crocodile - but we hit some questions when we get to the arms. We know these animals couldn’t pronate their hands (i.e. they can’t turn their wrists to make their hands face down), so it couldn’t have put its palms on the ground. Studies have also suggested that their wrists and forearms couldn’t have supported the animal walking on its knuckles, either. So...how did this animal stand and walk? It's widely assumed that it probably could stand on its hind legs, at least for a little while, but it's not clear if it could actually walk on them for long periods of time - especially with that huge sail and long torso. Ibrahim and colleagues suggested that this animal must have been semiaquatic. This was a really wild take; it would’ve made Spinosaurus not just the biggest theropod, but also the only semiaquatic one.

Ibrahim wasn't the first to suggest something along these lines. A 2010 study of Spinosaurus’ teeth suggested that they were in water a lot of the time. (Teeth need to be kept hydrated; part of why modern crocodilians can have teeth on the outside of their face is because they keep their mouths in water so much of the time.) And the skull shape, along with the teeth shape, had already suggested a diet of fish and other aquatic prey. Ibrahim's assertion was the strongest, though, and it wasn't without substantial controversy. Ibrahim and colleagues were active participants in the ensuing discussions, corresponding with other academics and publications constantly to defend their assertions.

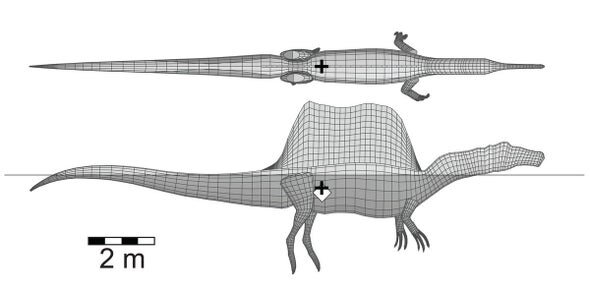

An image of the digital model of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus made by Henderson in 2018. The dark cross indicates where Henderson believes the animal’s center of gravity would’ve been, placing it much further back than previously suspected

This also led to a bunch of investigations into whether or not Spinosaurus could swim, and how well. A 2018 study by Donald Henderson looked at things like Spinosaurus’ lung capacity (based on its rib cage) and density to see if it could dive to pursue prey completely underwater. As summarized by articles with names like “Spinosaurus Was a Terrible Swimmer”, Henderson’s study asserted that Spinosaurus probably couldn't dive, and would’ve risked rolling over due to its huge sail. These sorts of findings made it seem pretty unlikely that Spinosaurus could really pursue prey or maneuver well underwater. On top of that, Henderson argued that Spinosaurus would’ve been able to walk around just fine on its hind limbs. It seemed settled.

But Ibrahim had to go and find more bones in 2018.

Described in a paper published just last year, in 2020, these new specimens included tail vertebrae that we’d never seen before - and they had long, thin spines. These gave Spinosaurus’ tail an overall shape somewhat like a tadpole’s, which pushed the argument back in the other direction. This tail - unlike any other theropod’s - was clearly specialized for at least a semiaquatic lifestyle. Several academics, along with very many paleoartists and even more paleofans, emphatically embraced the new-new proof that Spinosaurus was this crazy swimming theropod.

Diagram from the University of Detroit Mercy showing the newly-discovered tail vertebrae and the updated profile of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus. Just two years after “Spinosaurus Was a Terrible Swimmer”, we’re back to portraying it swimming underwater

But it still isn’t settled. As far as I’m aware, Henderson’s claim that Spinosaurus was “unsinkable” hasn’t been disputed by new findings yet, for example. Right now it seems like the pendulum is swinging more towards “it mostly spent its time on land, but probably hung out near water enough that it had several adaptations for wading” - but this is literally still being debated as I type this, and this summary might end up outdated in just another year or so. I can’t wait to see what more remains Ibrahim and others can find.

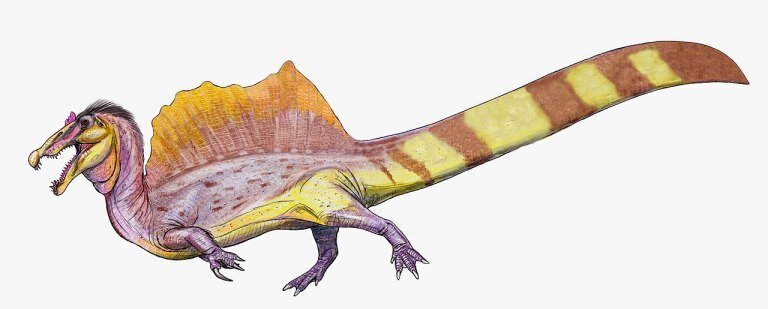

In the wake of these discoveries, there’s been so much awesome art that vividly embraces the weirdness of this animal that it’s hard to pick just one piece to showcase.

One of my absolute favorite pieces that’s attempting to depict Spinosaurus naturalistically and accurately to the current research is this animated walk cycle by Darrin Frederick:

Look at it!

Look at the way it bobs its head as it waddles!

And if you don’t think that’s just the coolest shit, you need to remember - the first digit on its hand? the one that it’s holding tucked close to its chest like a teeny-tiny chicken wing?

Yeah, here’s how big that is:

Image of a life-size replica produced by The Prehistoric Store. And that’s just the claw at the end of its first digit

You think you know shit about dinosaurs?

This is the largest carnivore to have ever walked the face of the Earth!

A nightmare crocodile-swan with a mohawk the size of a small car on its back, a jaw full of railroad spikes, and a tail like a sea monster!

Where’s your god now?

Spinosaurus is just a taste of what’s out there.

Bajadasaurus pronuspinax (which was discovered in 2010 and only formally named in 2019) is just your normal sauropod: long neck, stocky, likes plants, no biggie…oh and it has a series of insane spines growing out of its neck and stabbing forward, like a mane of backwards antelope horns.

A pair of Bajadasaurus, illustrated by Jorge A. González. While we don’t yet know for certain what their neural spines looked like in life, evidence from the related Amargasaurus suggests they had keratinous coverings - like horns

Therizinosaurus cheloniformus was a 30-foot-long turkey-giraffe that weighed as much as a hippopotamus, with goddamn machetes for fingers. And it’s one of the rare instances among theropods that evolved away from meat-eating!

A pair of Therizinosaurus poke around for food. Note the Velociraptor in the bottom-left corner for scale. Art by ABelov

You think I gotta stick with the big birds to blow your mind? Screw that-

Anurognathids were a group of small pterosaurus that looked like the porgs from STAR WARS EPISODE VIII: THE LAST JEDI but with a venus flytrap for a mouth. And covered in long whiskers.

Anurognathus ammoni chases a tasty treat, by Johan Egerkrans

Actually, let’s stick with pterosaurs for a hot sec. (Yes, I know they’re not classified within Dinosauria.) Since they, y’know, used wings to fly and usually had beaks, it’s easy for people to picture these animals like birds.

But most pterosaurs were quadrupedal on the ground.

And I don’t just mean that they technically had their forelimbs on the ground while they awkwardly shuffle-crawled around like modern bats. I mean they legit walked on all fours.

Tupandactylus imperator, illustrated by Elia Smaniotto - and yes, that head is the right size

In fact, some of them spent a lot of their time walking around on the ground, hunting with a head that’s almost as big as the rest of its body.

A typical azhdarchid (possibly Quetzalcoatl northropi) tries to keep its meal away from some hungry dsungaripterids - I swear, I’m not making these names up. Art by the prolific Mark Witton

Oh, and in case you didn’t notice from the above pictures: due to the way their wings folded up, their hands touched the ground either sideways or backwards.

While we’re talking about weird quadrupedal locomotion - I bet you’re picturing sauropod feet wrong. You’re imagining, like, an elephant’s foot, right? Just a big meaty can with some nubby toenails?

Turns out, they did the equivalent of walking on their tip-toes all the time. At least, on their forelimbs, which ended in this U-shaped thing with only one nail (jutting out to the side) and the rest of their fingers fused together, like a hoof made of meat - as illustrated here by Natee Puttapipat:

Oh, and as the artist notes, their hindlimbs ended in feet with claws that splayed out sideways like a tortoise. Which kinda makes sense for tortoises, because their wide bodies are real low to the ground with legs that jut out laterally and push to the side, and makes sense on sauropods whose legs are as straight as the Parthenon’s columns because fuck you.

You think you know shit about dinosaurs??

We've been so saturated with specific, outdated, and generic depictions of dinosaurs that they no longer feel alien or mysterious or fantastical. It’s easy to forget that these creatures lived an incomprehensibly long time ago, in a world so different from our own that it may as well have been on another planet. The Bahariya Oasis is located in Egypt, south of the Sahara Desert. And in this scorching, bone-dry place are the remains of the largest meat-eater to ever walk, which used to eat fish in precisely that region, whose anatomy is so wild that even after recovering most of its skeleton we’re still not completely sure how it moved around.

So when I say “put feathers on the monsters you grew up loving”, it’s not because I think those monsters should look more like fluffy birds (though, that might be pretty rad for some of them) - it’s cos you’re not thinking big enough when you’re imagining them.

You’re only seeing like 2% of the true power of dinosaurs.

Dinosaurs were so goddamn weird.

Weird shit is cool

If you embrace that weirdness - if you wade out into the abyss and really soak in all the madness that is the unfathomable diversity of life on Earth - then you can wield that insanity to make some neat stuff.

Like this art from a recent Magic: The Gathering card that blew me away when I saw it.

The art for “Leyline Tyrant”, by Chase Stone

We’ve all seen a million and a half dragons. They’re as common and recognizable a monster as T-rex.

But I took one look at this piece and went “This guy fuckin’ gets it”. Not just because the subsurface scattering on those wings is sublime, and not just because the fire radiating out through cracks(?) in its neck is a cleverly understated way to communicate “fire-breathing dragon”. I knew this guy gets it, because his dinosaurian take on a dragon has all this weird shit.

The first thing that jumped out at me were those forelimbs, which look like they came straight off a Spinosaurus (the size and arrangement of the claws match almost exactly). And just like a Spinosaurus, it doesn’t look like it could rotate them to face the ground - which already suggests this thing is going to move and stand differently from your typical lizard-with-wings dragon schema. (If someone draws arms that can’t pronate, you know they’re a paleoartist.)

And the next thing that jumped out at me, somehow even before those vertebral pillars running down its back, is the bony blocks growing out its chin and snout. These immediately give it a distinctive silhouette, and simultaneously look plausible and baffling. Mean-looking pointy horns are obvious; strange-shaped growths make you wonder.

And lastly, of course, look at that glorious stream of bones coming out of its spine. Again, Stone’s decision to make them more squared-off adds so much to the design. I have no idea how he came up with this concept, but it’s like he imagined fossils of this thing, then imagined people trying to figure out what was going on with those spines (“A sail? A big hump? Maybe they ended in spikes that didn’t fossilize?”), and then picked the weirdest answer he could come up with (i.e. nothing at all - just the spines jutting out). Why would this animal have these things? I have no goddamn idea, and that makes this so much more compelling than Red And Spiky Dragon Design #57032.

Finally, in case it wasn’t clear from all the sweet art throughout this piece:

Paleoart is amazing.

Paleoart is an incalculable blessing to the field of creature design.

Paleoartists combine incredible fluency in depicting the natural world with a passion for portraying things that none of us will ever see in reality. These people know shit you’ve never even heard of.

Check out Simon Stålenhag. That’s right, the dude I mentioned before who did STRANGER THINGS-tinged horror so well that one of his art books inspired a TV series also has some of the most vivid paleoart you’ve seen.

Check out Terryl Whitlach, whose ability to infuse fictional anatomy with naturalistic whimsy (or maybe the other way around?) has led to her designing aliens for Star Wars (and more).

Check out James Gurney - not only is he the talent behind Dinotopia, he also literally wrote the book on imaginative realism (some principles of which I’ve talked about here).

Check out RJ Palmer. Dude loves him a freaky monster as much as he loves Pokémon. In fact, he did the design work for the “live-action” pokémon we saw in DETECTIVE PIKACHU.

Check out every paleoartist I linked to in this piece.

Jump all the way down every rabbit hole. Get inspired by all the weirdness you find.